About Performance

Milosav Buca Mirković

THE IMPURE BLOOD BY LIDIJA PILIPENKO

“Dare to be yourself!” Andre Gide

In her libretto, depicting poetical, inner dramatization, Lidija Pilipenko gives life to extraordinarily new and existentially committed Bora Stanković.

It has been already noted (by Jovan Skerlić, Velibor Gligorić, Isidora Sekulić, Jovan Dučić, Tin Ujević …) that Bora Stanković’s artistic procedure presented in his time great novelty and originality, especially in the field of psychoanalysis. Stanković was the first one in our literature who dared to reveal the most intimate aspects of human life, until then neglected and ignored. For instance, erotics and sensuality were considered to be vulgar and unliterary motives. However, Stanković freely and openly portrayed fires and flames of human senses and passions, but never slipped into vulgarity and naturalism. Lidija Pilipenko goes a step further in her poetical courage; she releases even Bora Stanković himself from naturalism, sociologism, folklore traits and the epoch overwhelmed with defiance and melancholy. In her interpretation, Bora is neither brother nor peer, neither hidden nor unhidden image of Hadži Toma, Mitke, Master Mladen, Miron, Jovče in whose velvet gamma lives the spirit of the past and the old Gospel. The whole conception by Lidija Pilipenko (libretto, readaptation, direction, music selection and choreography) is intended to describe and to illustrate the characters in The Impure Blood in a way Dostoyevsky portrayed his characters in Demons. Certainly, the motive is taken from Bora’s novel The Impure Blood, but the thematization is realized in the unique manner of Lidija Pilipenko. It seems like colors and movements, sounds and silences reflect characters’ own authentic feelings and not have much to do with Bora Stanković who himself was limited by his own epoch and catharsis, his falls and raisings.

“Every man, philosopher included, ends in his own finger-tips. That’s the end of his man alive... The whole thing about the Spirit is not anything else, but just a tremulation upon the ether” – wrote D.H. Lawrence.

“Bora takes us” – wrote Isidora Sekulić in 1952 – “whether we like it or not into his vilayet”, left, right as on the tuning waves of a genuine dramatic ballet. He takes us “at the bottom of his heart”.

Therefore this poetics contains something inherent to Andrić’s poetics: phenomena of evil, darkness, grief, and ugliness alternate as phases of lunar fever, opaque and dense moonlight upon the tombstones, the necropolises, the cemeteries, the catacombs. Forgetiness as a lifestyle is not immanent to our Bora, however, the intoxicating cup of life is always by his hands, even if being pushed to the very edge of scaffolds, gallows, battlefields, salvages.

Viewed by Lidija Pilipenko, that shaded torso, in the same way as Dostoyevsky’s Karamazovs, does not seek recovery, but salvation. That inevitability is burning, ardent, explosive: it is the power of Eros that destroys system of repression, through only possible means: fantasy and poetry.

What remain are colors and sounds, movements and interruptions, the most trustful witnesses (and contributors) of Lidija Pilipenko’s Glory. To her and to her more glorious hero Bora Stanković we may apply Boris Pasternak’s words: “To live – is not to cross a field”.

BORISAV STANKOVIĆ

March 23(31), 1876 Borisav Stanković was born into an artisan’s family, in Vranje, of father Stojan, and of mother Vaska. Bora’s parents were close relatives, so they had to wait a long time for bishop’s “blessing” and approval to get married. His fraternal grandfather, Ilija, was a shoemaker in Vranje, married with Zlata, a daughter of prominent merchant family Jovičić. His father, Stojan, was a shoemaker in the Upper Mahala and a well-known singer.

1881 At the age of five he lost his father, at the age of seven his mother.

1883 He entered the primary school in Vranje.

1888 He entered the lower gymnasium in Vranje.

1892 He finished the gymnasium fourth year. His professors were Jaša Prodanović, Draža Pavlović, Milivoje Simić.

1894 Sombor’s literary magazine “Golub” published his poems A Wish and Mother at the tomb of her only son, signed with Borko.

1896 His grandmother Zlata died. The last one who cared for me. My last hope, the last branch of my family, my grandmother has passed away! Always alone, with no father, nor mother, no brother, nor sister, with no one around me. Except her. She brought me up from “the very first day of my life”. And now she has gone forever.

He finished gymnasium eight year in Niš with good grades. That same autumn, he came to Belgrade and entered the Law Scholl – Economy Department of the Grand Scholl.

1897 He was employed as an official in the State Printing Office.

1898 In literary magazine “Iskra” he published his first story Stanoja. Later, in the same magazine he published another two stories: St. George’s Day and The First Tear, and in Sarajevo’s literary magazine “Nada” – Secret Pains.

1899 He published his first collection of stories From the Old Gospel.

1900 The first production of Koštana at the Belgrade National Theatre.

On May 1, 1900 he was appointed an official in the Ministry of Education.

Later, he was transferred to the National Theatre of Belgrade, where he was employed as an account controller.

1901 He published seven stories.

He was dismissed from his post “because of his negligence”; two days later he was appointed an official in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

In October 1901, the revised Koštana had a great success at the National Theatre, especially due to the positive critique by Jovan Skerlić.

1902 His three books were published: The Old Times, God’s Children and Koštana.

On January 27, he married Angelina Milutinović.

1903 He published his third novel Master Mladen in literary magazine “Kolo”.

At the beginning of the year, he was transferred to the Ministry of Finance (where he stayed until 1913) as an “ inspector of the state customs office” in the Bajloni Brewery.

His first daughter, Desanka, was born. Her godfather was Branislav Nušić.

He received fellowship from the Ministry of Education and, with his scribe salary from the Ministry of Finance and a subsidy from “Financial Review”, left for Paris.

1904 After a year his fellowship was cancelled and he was “repatriated” to Serbia. Revolted, he quitted the civil service, and with a group of writers who shared the same feeling of being “needless in Serbia” took part in protest-evenings. In the midst of polemic with Radoje Domanović, as a sign of protest, he wrote a letter to Nikola Pašić.

His second daughter, Stanka, was born. Her godfather was Janko Veselinović.

1905 He revised Koštana and published it in literary magazine “Brankovo Kolo”.

1906 He published Stories from my homeland.

He was employed as a third class tax collector in the Belgrade Tax Services Office.

1907 He published new version of The Impure Blood in literary magazine “Delo”.

1909 He finished The Impure Blood. Since his attempts to find a publisher were unsuccessful he published the novel in installments, in literary magazine “Letopis Matice Srpske”.

1910 As he was rejected by the Kolarac Foundation, he decided to publish his first novel, The Impure Blood, on his own. Therefore, he posted an ad, which Matoš published in Zagreb’s literary magazine “Savremenik”.

1911 He was appointed a first class inspector of the State Customs Office.

1912, He toured Sophia with the National Theatre production of Koštana.

1913 He was transferred to the Ministry of Education and Religion, on a post of an official in the Department of Church Affairs.

His third daughter, Ružica, was born.

He published second, revised edition of God’s Children.

1915 He was freed from military service, and spent some time in Vranje, then in Niš, where the whole government and the administration were located.

As an official in the Department of Church Affairs he was appointed to accompany the guards in charge of the Transfer of Relics of Stefan Prvovenčani from Studenica to Peć.

His family stayed in Kraljevo; in Peć he left the Army that proceed towards Albania and went to Podgorica, then to Cetinje.

1916 After the capitulation of Monte Negro, he passed through Bosnia to Belgrade, but was stopped in Derventa. All his manuscripts stayed in Niš.

Thanks to Kosta Herman, former editor of Sarajevo’s literary magazine “Nada”, at that time “Assistant Chief of a Military Governor for occupied Serbia” Stanković escaped interniation and went back to Belgrade.

1916 – 1918 He wrote articles for “The Belgrade News”.

1918 The Impure Blood was published in Geneva within the edition of “Yugoslav Literature”.

1919 He published his book of memories Under the Occupation in the newspaper “Dan”.

In numbers of articles, “Politika” criticized Stanković for his writings in “The Belgrade News”.

1920 He was appointed an official in the Art Department of the Ministry of Education.

1922 His memories Under the Occupation and The Shirkers were published in installments in the daily journal “Novosti”.

He was appointed a chief in the Statistics Department of the Ministry of Education.

1924 The twenty-fifth anniversary of his work was marked with the series of suitable manifestations.

The third, revised edition of Koštana was published.

My Compatriots – his last published novella.

He was appointed an official in the Department of Primary Education in the Ministry of Education. For that reason he complained to the State Council, which refused his complaint.

1927 Marika Jeminović, known as Koštana, through her husband Maksuta demanded of him to pay the royalties claimed by her for showing Koštana. Echoes and reactions were published by almost all the newspapers. In its comment of March 13, “Politika” wrote: “One person wants a writer! And wants money from the writer! Wants the writer pay it for he wrote!”

By the decision of the Ministry of Education dated March 30, B. Stanković was retired.

Premiere of Tašana at the National Theatre.

On October 21, in front of the theatre building, he got sick.

He was driven to his home, and passed away on the same day, just before midnight.

He died at 52.

Taken from Borisav Stanković (1876 – 1927) – catalogue of the exhibition held in the Belgrade City Library on the occasion of marking the 80th anniversary of the death of a great writer. Author of the exhibition: Olga Krasić-Marjanović

October 2007

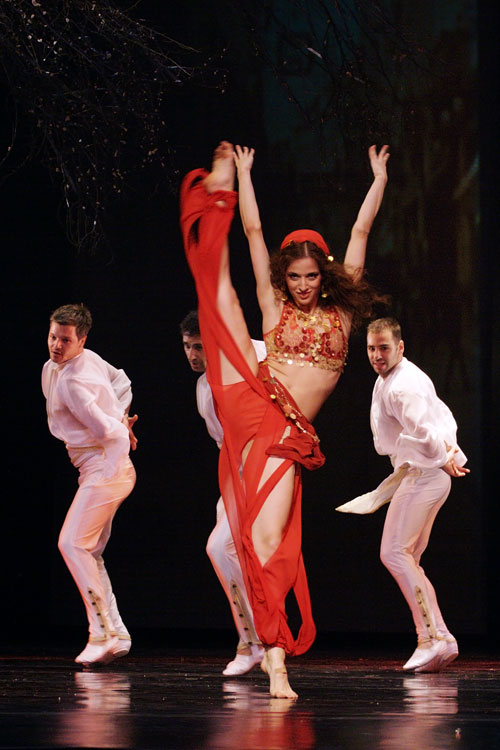

LIDIJA PILIPENKO

LIDIJA PILIPENKO

Lidija Pilipenko - artist, prima ballerina, and choreographer, spent most of her professional career at the National Theater Ballet. After her specialization in London with Ninette de Valois she ventured to choreography. Already having brilliant career as a prima ballerina of the National Theatre Ballet, she proved herself to be one of the top choreographers in the country. She created the following ballets to the music by Yugoslav composers: Banović Strahinja and Jelisaveta by Zoran Erić for the Belgrade Theatre, The Eternal Bachelor, and The Choosy Girl by Zoran Mulić for the Theater in Novi Sad. For Banović Strahinja she received choreography award at the Biennale in Ljubljana, in 1981. She also received choreography award for the two full-evening ballets, Jelisaveta and The Eternal Bachelor.

Then followed Samson and Delilah by Camille Saint-Saens, for which she received the National Theater Award. The piece was presented on the occasion of the opening of the ballet season after the theater reconstruction, in1989. She also created two world premiers: Resurrection to the music by Gustav Mahler’s 2nd Symphony; Lady of the Camellias to the music by Giuseppe Verdi. In 1994 she staged for the National Theatre Ballet El Amor Brujo by Manuel de Falla and Scheherazade by Nikolai Rimski-Korsakov. Soon after, in 1998, A Women to the music by S. Rachmaninov. With same success she has made choreographies for several musicals: The Story of a Horse, My Boyfriend, The Gypsies Fly to the Sky, I love My Wife, The Wind Will Cease, etc... for the operas: Carmen, Aida, The Bat, etc, and for TV and film. In 1999, for the Twentieth Century Program of the National Theater in Belgrade she staged two one-act ballets: The Images to the music by A. Schoenberg and The Cage to the music by G. Mahler(2007 renewed version). In 2000 she staged The Legend of Ohrid by Stevan Hristić, in 2004 Tchaikovsky the Poet, rewarded as the best performance of the season 2003/2004. She received the award for the life opus in 2001, the Award Dimitrije Parlić in 2004 and the National award for the culture contribution, 2007.

She held the position of Head of the National Theatre Ballet from 1992 – 1993 and from 1997 – 2000 .

A WORD FROM THE AUTHOR

In Bora Stanković’s work we clearly recognize his whole self. His art is deeply rooted in his genius. While reading his literature, we easily realize ambiguity between the artist (creator) and the man troubled by worries of everyday life. Devotion to family, provincial mentality and patriarchal moral values turned to be a heavy Sizif’s stone over his shoulders, and along with his exceptional sense of observation, interpretation and imagination, real essence of his gift, made him live his whole life as a prisoner of his own being.

When portraying his characters, either affirmatively or negatively, he used to do it in a way to live with them, to suffer with them and never to judge them.

Who was Bora Stanković? How to discover the secret of his complex mind and to understand why, at the end of the ninetieth century and at the beginning of the twentieth century, it took him ten years to write The Impure Blood? A full evening ballet in two acts, which main character is Bora Stanković, offers librettist inexhaustible inspiration to portray Bora, great master of Serbian literature.

It is astonishing how a man-writer with exceptional courage and lucidity observes and reveals the deepest, the most inner secrets of a woman living under the imposed norms, without words, without questions, without freedom of decision. While writing about her, Bora “runs away” from the inherent limitations of words, however, while dreaming he turns back to her, to a woman.

I want to take Bora into the world of his own imagination, to make him spend lives of his heroes right in front of our eyes, because only in this way we can realize how through characterization of Sofka, Koštana, Tašana and other heroes great writer experienced liberating power of his own unconscious mind.

Feeling great empathy for his heroes, Bora Stanković described their characters and destines, thus revealing his own personality, surroundings in which he lived and power of untold and untouchable truths. Critics, criticizers, friends and enemies, judged his works from admiration to severe insults; often being aware of great injustice they had done to him. Fortunately, a great number of analyzers, theoreticians of Bora’s work, as well as his biographers, had to confess (during his lifetime), that his gift exceeded his own time. Bora Stanković was a forerunner of modernity, at the very beginning of the twentieth century. Our famous writer, Ivo Andrić, Nobel prizewinner, explained nicely who was Bora Stanković.

Why The Impure Blood? Why this title of the full evening ballet? In a word – blood is common motive of all his works.

Siniša Paunović, a writer, quotes in his book Velibor Gligorić’s words referring to Bora Stanković: “In his view fundamental nature of human existence is yearning for life in all its beauty and brightness. To enjoy the sweetness of life fully, passionately, is nothing else but longing for beauty and harmony, for life’s joy. And this is the greatest life principle, the greatest value of being alive. That’s why he felt with an exceptional exaltation springtime of life, springtime of the human spirit and that’s why nearest and dearest to him was a man of rich imagination and sensibility. In the works of Bora Stanković, desire for personal freedom and happiness is very intensive”.

Preoccupied with The Impure Blood, Bora defines blood as human curse, curse that excites, that leads to madness and finally destroys. And that’s why the full evening ballet about Bora Stanković is titled after his famous work - The Impure Blood.

Premiere performance

Premiere, June 15, 2007 / Main Stage

Ballet in two acts, 8 scenes

Libretto Lidija Pilipenko

After The Works By Borisav Stanković

Music Stevan S. Mokranjac, Petar Konjović, Vasilije Mokranjac, Stevan Hristić

Choreography, Direction Lidija Pilipenko

Costumes Božana Jovanović

Sets Boris Maksimović

Music Compilation Lidija Pilipenko, Author

Video & Music Production Petar Antonović

Music Collaborator Igor Karakaš