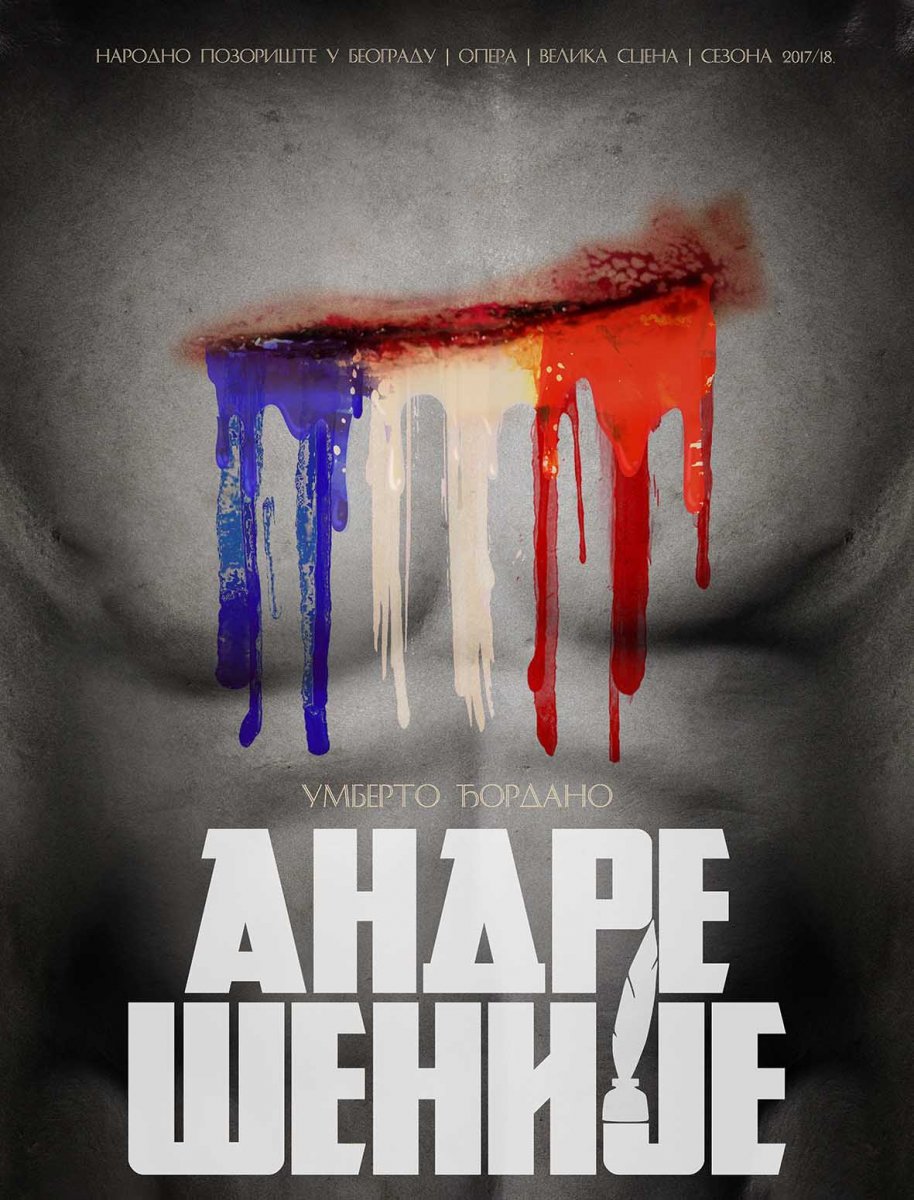

ANDREA CHÉNIER

opera by Umberto Giordano

About Performance

UMBERTO GIORDANO (1867-1948)

UMBERTO GIORDANO (1867-1948)

Umberto Giordano was an Italian composer at the period of Verismo and Neo-Romanticism. Giordano was born in the south of Italy and he studied music at the Naples Conservatory of Music, mentored by Paolo Serrao. While still a student, influenced by Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana, Giordano composed his first opera Marina (in 1888) for the one-act opera competition promoted by the music publisher Sonzogno. Although Mascagni won in the competition with his Cavalleria rusticana, Giordano was placed sixth, which brought him a contract with Casa Sonzogno. Conzogno commissioned him to write Mala vita (Wretched Life), a verismo opera about a worker afflicted by tuberculosis who pledges to help a prostitute if he is cured from his illness, which was performed with success in Rome in 1892. His next opera Regina Diaz (Queen Diaz) was a failure and was withdrawn from the repertory after having only two performances. Giordano soon moved to Milan and returned to verismo style. He became famous in 1896 with Andrea Chénier, which triumphed at its premiere. Very soon, the opera became popular outside of Italy; it was staged in Berlin and London, where it was performed in English. While still enjoying his success with Chenier, Giordano wrote Fedora in 1898, based on Victorien Sardou’s play, which also became successful. It was followed by numerous operas, which are now almost forgotten, amongst which are Madame Sans-Gêne and La cena delle beffe, with the libretto written by Sam Benelli, which were performed in La scala in 1924. Giordano was Mascagni’s successor in the verismo style; success and fame were on his side while the interest for verismo drama was popular. He died in Milan in 1948, at the age of 81.

ANDREA CHENIER, A TRAGIC REVOLUTIONARY

Andrea Chénier is a passionate love story of conviction and sacrifice, set against the backdrop of the turbulent real life events of the French Revolution — a time when up became down, and Parisians never knew which day might be their last.Opera in four acts by Umberto Giordano, set to an Italian libretto by by Puccini's regular collaborator Luigi Illica, was first performed on 28 March 1896 at La Scala, Milan. Giordano perfectly captures the atmosphere of Paris pre- and post-Revolution, through music including the popular revolutionary songs 'La Carmagnole' and the 'Marseillaise'. Andrea Chénier is a poet, brought up in the lap of luxury, but hugely unhappy with the social inequality around him. He’s in love with Maddalena, a beautiful young aristocrat, but her family's servant Gérard, who resents the privileged upper classes, also harbours a deep passionate love for her. As the opera progresses, Gérard becomes an integral player in the French Revolution and uses his new power to condemn Chénier to death. The story is based loosely on the life of the French poet André Marie Chénier (30 October 1762 – 25 July 1794), associated with the events of the French Revolution of which he was a victim. His sensual, emotive poetry marks him as one of the precursors of the Romantic movement. His career was brought to an abrupt end when he was guillotined for supposed "crimes against the state", near the end of the Reign of Terror. The character Carlo Gérard is partly based on Jean-Lambert Tallien, a leading figure in the Revolution. Chénier was born in the Galata district of Constantinople where his father, Louis Chénier, was appointed to a position equivalent to that of French consul. His mother was of greek origin. When André was three years old, his father returned to France. In 1783 he enlisted in a French regiment at Strasbourg, but the novelty soon wore off. He returned to Paris before the end of the year, and mixed in the cultivated circle, including the painter Jacques-Louis David. He had already decided to become a poet, and worked in the neoclassical style of the time. He was especially inspired by a 1784 visit to Rome, Naples, and Pompeii. For nearly three years, he studied and experimented in verse. He wrote mostly idylls and bucolics, imitated to a large extent from Theocritus, Bion of Smyrna and the Greek anthologists. He mixed classical mythology with a sense of individual emotion and spirit.

Apart from his idylls and his elegies, Chénier also experimented with didactic and philosophic verse, and when he commenced his Hermès in 1783 his ambition was to condense the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot into a long poem somewhat after the manner of Lucretius. Now extant only in fragments, this poem was to treat of man's place in the universe, first in an isolated state, and then in society. Another fragment called "L'Invention" sums up Chénier's thoughts on poetry: "De nouvelles pensées, faisons des vers antiques" ("From new thoughts, let us make antique verses"). Chénier remained unpublished. In November 1787 an opportunity for a fresh career presented itself. The Chevalier de la Luzerne, a friend of the Chénier family, had been appointed ambassador to Britain. When he offered to take André with him as his secretary, André knew the offer was too good to refuse, but was unhappy in England. He bitterly ridiculed "... these English. A nation for sale to whoever can pay for it. Going from country to country and out to the whole world, offering its ignoble joy and its coarse splendor…." The events of 1789 and the startling success of his younger brother, Marie-Joseph, as political playwright and pamphleteer, concentrated all his thoughts upon France. In April 1790 he could stand London no longer, and once more joined his parents at Paris. France was on the verge of anarchy. A monarchien believing in a constitutional monarchy for France, Chénier believed that the Revolution was already complete and that all that remained to be done was the inauguration of the reign of law. Though his political viewpoint was moderate, his tactics were dangerously aggressive: he abandoned his gentle idyls to write poetical satires. His prose "Avis au peuple français" (24 August 1790) was followed by the rhetorical "Jeu de paume", addressed to the radical painter Jacques-Louis David. In the meantime he orated at the Feuillants Club, and contributed frequently to the Journal de Paris from November 1791 to July 1792, when he wrote his scorching iambs to Jean Marie Collot d'Herbois, Sur les Suisses révoltés du regiment de Châteauvieux. The insurrection of 10 August 1792 uprooted his party, his paper and his friends, and he only escaped the September Massacres by staying with relatives in Normandy. In the month following these events his brother, Marie-Joseph, had entered the anti-monarchical National Convention. André raged against all these events, in such poems as Ode à Charlotte Corday congratulating France that "one scoundrel less creeps in this mire". At the request of Malesherbes, the defense counsel to King Louis XVI, Chénier provided some arguments for the king's defense. After the king's execution he sought a secluded retreat on the Plateau de Satory at Versailles and only went out after nightfall. There he wrote the exquisite poem Ode à Versailles. His solitary life at Versailles lasted nearly a year. On 7 March 1794 he was arrested on suspicion of being the aristocrat marquise who had fled. He was taken to the Luxembourg Palace and afterwards to the Prison Saint-Lazare. During the 140 days of his imprisonment he wrote a series of iambs (in alternate lines of 12 and 8 syllables) denouncing the Convention, which "hiss and stab like poisoned bullets", and which were smuggled to his family by a jailer. In prison he also composed his most famous poem, "Jeune captive", a poem of of despair, inspired by the misfortunes of his fellow captive the duchesse de Fleury. Ten days before Chénier's death, the painter Joseph-Benoît Suvée completed the well-known portrait of him. Maximilien Robespierre, who was himself in dangerous straits, remembered Chénier as the author of the venomous verses in the Journal de Paris and had him hauled before the Revolutionary Tribunal, which sentenced him to death. Chénier was one of the last people executed by Robespierre. At sundown, Chénier was taken by tumbrel to the guillotine at what is now the Place de la Nation. He was executed along with Françoise-Thérèse de Choiseul-Stainville, Princesse Joseph de Monaco, on a charge of conspiracy. Robespierre was seized and executed only three days later. Chénier, aged 31 at his execution, was buried in the Cimetière de Picpus. During Chénier's lifetime only his Jeu de paume (1791) and Hymne sur les Suisses (1792) had been published. For the most part, then, his reputation rests on his posthumously published work, retrieved from oblivion page by page. Critical opinions of Chénier have varied wildly. He experimented with classical precedents rendered in French verse to a much greater extent than other 18th-century poets; on the other hand, the ennui and melancholy of his poetry recalls Romanticism. In 1828, Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve praised Chénier as a heroic forerunner of the Romantic movement and a precursor of Victor Hugo. Chénier, he said, had "inspired and determined" Romanticism. Many other critics also wrote about Chénier as modern and proto-Romantic. However, Anatole France contests Sainte-Beuve's theory: he claims that Chénier's poetry is one of the last expressions of 18th-century classicism. His work should not be compared to Hugo and the Parnassien poets, but to philosophes like André Morellet. Paul Morillot has argued that judged by the usual test of 1820s Romanticism (love for strange literature of the North, medievalism, novelties and experiments), Chénier would have been excluded from Romantic circles. The poet José María de Heredia held Chénier in great esteem, saying "I do not know in the French language a more exquisite fragment than the three hundred verses of the Bucoliques" and agreeing with Sainte-Beuve's judgment that Chénier was a poet ahead of his time. Chénier has been very popular in Russia, where Alexandr Pushkin wrote a poem about his last hours based on Latouche and Ivan Kozlov translated La Jeune Captive, La Jeune Tarentine and other famous pieces. Chénier has also found favor with English-speaking critics; for instance, his love of nature and of political freedom has been compared to Shelley, and his attraction to Greek art and myth recalls Keats. Chénier's fate has become the subject of many plays, pictures and poems, notably in the opera Andrea Chénier by Umberto Giordano, the epilogue by Sully-Prudhomme, the Stello by Alfred de Vigny, the delicate statue by Denys Puech in the Luxembourg, and the well-known portrait in the centre of Muller's Last Days of the Terror.

Jovan Tarbuk

ĐORĐE PAVLOVIĆ

ĐORĐE PAVLOVIĆ

Đorđe Pavlović was born in 1965 in Loznica. He obtained his BA and MA degrees in conducting at the Faculty of Music Art in Belgrade in the class of Professor Jovan Šajnović. Pavlović has been working in the National Theatre Opera since 1992, where he conducted in operas The Bat, The Barber of Seville, The Troubadour, Traviata, Rigoletto, Attila, Nabucco, Don Carlos, Adriana Lecouvreur, La Boheme, Eugene Onegin, Melancholic Dreams оf Count Sava Vladislavić and ballets The Sleeping Beauty and The Taming of the Shrew. In period 2000 – 2006, with the Choir of the Opera, Pavlović staged first productions of three comprehensive pieces, Heavenly Liturgy, Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, and Holiday Evening Service by Svetislav Božić. Besides his work on operatic repertoire, he has been very active in concerts in our country and abroad, where he was engaged in promotion of Serbian music. Some of his performances outside the country were with the Ukrainian Radio Orchestra at Kiev Music Fest, as well as with Oxfordphilomusica Orchestra at the concert in Regent Hall in London. He has been a permanent guest conductor of State Symphony Orchestra from Zaporozje; Since May 2006, he has been working as a head conductor in Borislav PašćanYouth Philharmonic. He gave numerous concerts with the Youth Philharmonic and won the Gold Plaque of Kolarac’s Legacy Award, at the celebration of 130th Anniversary of the cultural institution (in 2008), and Golden Ring of the Cultural and Educational Community of Serbia for his permanent contribution to culture (in 2009). He belongs to a generation of Serbian conductors who focus their spiritual and artistic growth on incessant source of national music by enriching their repertoire with pieces of spiritually similar music cultures.

GIANDOMENICO VACCARI

GIANDOMENICO VACCARI

Giandomenico Vaccari is an italian opera director. In his career he was Artistic director at San Carlo Theatre in Naples, Verdi Theatre in Trieste and Verdi Theatre in Salerno and Artistic Consultant in Opera Theatre in Rome. Since 2005 till 2012 he was chairman and artistic director at Petruzzelli Theatre in Bari. He worked also as secretary artistic in Comunale Theatre in Bologna and in Carlo Felice Theatre in Genova. Now he is Artistis director of Opera in Puglia and President of Orchestra Oles. In 1998 he was awarded the Luigi Illica Prize for the production of La Fiamma by Respighi performed in Rome. As a director Vaccari made his debut in Lecce in 1982 with Barber of Seville. He worked with great italian directors like Maurizio Scaparro and Mauro Bolognini. In 2011 Vaccari comes back to the direction with Carmen at Toronto. In 2013 and 2014 he directed La Fanciulla del West and Don Giovanni at Castleton Festival in Virginia Usa. In 2014 Vaccari opend the lyric season in Teatro Pavarotti of Modena with Rigoletto. In 2014 and 2017 he directed Tosca and Pagliacci in Busan and Seoul, South Korea, conducted by Maestro Dejan Savic. In 2016 and he realized Norma at Bellini Theatre of Catania and Nabucco in Salerno where comes back in 2017 with Norma. In 2017 he realized Cavalleria Rusticana for Skopye Opera. With Andrea Chenier Vaccari makes his debut in Belgrade Opera.

Synopsis

ACT I

Spring, 1789, at the Château de Coigny near Paris. Gérard, servant to the Countess de Coigny, mocks the aristocracy and their manners. Observing his father struggle with a piece of furniture, Gérard laments the suffering of all servants under their arrogant masters (“Son sessant’anni”). Maddalena, the Countess’s daughter, appears and Gérard realizes how much he loves her. Busy with preparations for a soirée that evening, the Countess scolds Maddalena for not yet being dressed. Maddalena complains to her servant, Bersi, about the discomfort of the current fashions and then runs out to change. Among the guests to arrive is Fléville, a novelist, who has brought with him the rising poet Andrea Chénier. After the Abbé relates the latest depressing news from Paris, Fléville enlivens the party with a pastorale he has written for the occasion. Maddalena then teases a reluctant Chénier into improvising a poem (“Un dì all’azzurro spazio”). Chénier scandalizes the guests with his criticism of the indifference of the clergy and the aristocracy to the suffering of the impoverished. The guests’ gavotte is interrupted by Gérard, who brings in a group of starving peasants. The Countess orders Gérard out along with the rabble. The guests are then invited to return to the gavotte, but they depart instead, and the Countess is left alone.

ACT II

Spring, 1794, along the Cours-la-Reine in Paris. The Revolution has begun, and the Reign of Terror is in full force. To fend off the Incredibile, a spy, Bersi pretends to be a daughter of the Revolution (“Temer? Perchè?”). The Incredibile is not deceived and notices that Chénier is waiting for someone in the Café Hottot. Chénier is joined by his friend Roucher, who has brought a passport so that Chénier may leave the country safely. Chénier says his destiny is to remain to find the love he has never had and to discover who has been writing him anonymous letters (“Credo a una possanza arcana”). A procession of dignitaries led by Gérard interrupts their conversation. The Incredibile takes Gérard aside to ask about the woman he is looking for. Gérard describes Maddalena to him. Meanwhile, Bersi asks Chénier to wait at the café for someone who wants to meet him. Maddalena appears and reveals to Chénier that it was she who wrote the letters. They pledge to love each other until death (“Ora soave”). The Incredibile, having seen Chénier and Maddalena together, brings Gérard to the scene. Gérard is wounded as Chénier defends Maddalena. Gérard, however, recognizes Chénier and sends him away, asking him to protect Maddalena. When the gathering crowd asks who wounded Gérard, he answers that his assailant was unknown.

ACT III

July 24, 1794, in the courtroom of the Revolutionary Tribunal. Mathieu, a revolutionary, is unsuccessfully urging the crowd to donate to the cause. Gérard, recovered from his wound, makes an impassioned plea for the motherland. Madelon, an old woman who has already lost her son and a grandson in the war, offers her last grandson as a soldier (“Son la vecchia Madelon”). As the crowd disperses, the Incredibile appears. If Gérard wants to have Maddalena, the Incredibile insists, he must first arrest her lover, Chénier. As Gérard writes the accusation, he is filled with remorse at the bloodshed he has caused in his rise to power. He concedes that his new master is passion (“Nemico della patria”). No sooner does he hand Chénier’s indictment to the court clerk than Maddalena appears. Gérard admits that he has laid a trap for her and that he loves her. Maddalena offers herself to Gérard if he will save Chénier. She has been a fugitive, her mother was killed in the Revolution and their home was burned (“La mamma morta”). Touched by her love for Chénier, Gérard promises to try to save him. The Tribunal convenes with an unruly mob in attendance. Chénier pleads for his life (“Sì, fui soldato”) and Gérard admits to the judges that the accusation he wrote was false. Nevertheless, Chénier is sentenced to death and taken away.

ACT IV

July 25, 1794, in the ruins of Paris’ St. Lazare prison. Chénier reads a final poem (“Come un bel dì di maggio”) to his friend Roucher, who then bids him a final farewell. Gérard and Maddalena are met by the jailer, Schmidt, whom Maddalena bribes with some jewels to allow her to take the place of another young woman sentenced to death. Gérard leaves to once again plead Chénier’s case with Robespierre. Maddalena tells Chénier she is there to die with him. As the day dawns, they share one final moment together (“Vicino a te”) before being taken to the guillotine.

Premiere performance

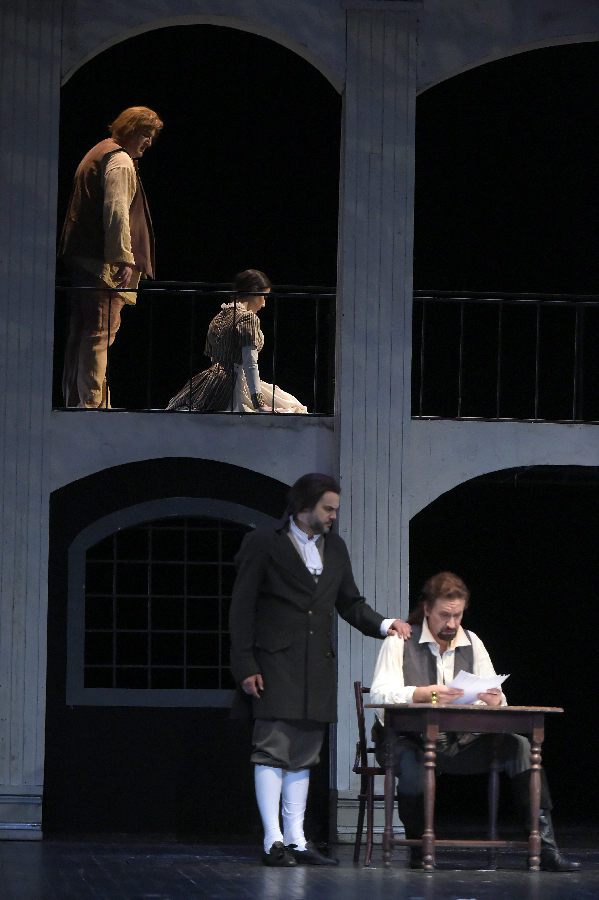

Premiere 23 June 2018 / Main stage

Conductor Đorđe Pavlović

Stage Director Giandomenico Vaccari, as guest

Set Designer Kuzman Popov, as guest

Costume Designer Asya Stoimenova, as guest

Premiere Cast:

Andrea Chénier, a poet Dušan Plazinić / Janko Sinadinović / Alekandar Dojković

Carlo Gérard, a servant Miodrag D. Jovanović / Dragutin Matić

Maddalena di Coigny Ana Rupčić / Jasmina Trumbetaš Petrović

Bersi, her maid Ljubica Vraneš

La comtesse di Coigny Dubravka Filipović / Tamara Nikezić

Pietro Fléville, a novelist Marko Pantelić*

Mathieu, a sans-culotte Mihailo Šljivić

The Abbé, a poet Siniša Radin*

The Incredible, a spy Darko Đorđević

Roucher, a friend of Chénier Vuk Matić

Schmidt, a jailer at St. Lazare Sveto Kastratović

Madelon, an old woman Nataša Rašić

Fouquier-Tinville, the Public Prosecutor Miroslav Markovski

Dumas, sudija Milan Mladenov*

Master of the Household Milan Mladenov*

CHOIR, ORCHESTRA AND BALLET OF THE NATIONAL THEATRE IN BELGRADE

Members of Children’s Choir „Horislavci“

* member of the „Borislav Popović” Opera studio

Assistant Stage Director Ivana Dragutinović Maričić

Assistant Stage Director Ana Grigorović

Concertmaster Edit Makedonska / Vesna Jansens

Chorus Master and Stage Music Chief Djorđe Stanković

Stage Manager Ana Milićević

Choreographer Miloš Kecman

Prompter Silvija Pec / Kristina Jocić

Music associates: Srđan Jaraković, Gleb Gorbunov

Chorus Instructor Tatjana Ščerbak Pređa

Translation Maja Janušić

Producers Maša Milanović Minić i Natalija Ignjić

Extra's Chief Zoran Trifunović

Ballet duo Ana Ivančević and Miloš Kecman

Make-up Marko Dukić

Light Design Nait Ilijazi

Sound Design Tihomir Savić

Set realisation Miraš Vuksanović, Jasna Saramandić

Costume realisation Katarina Aleksandra Pecić

Stage Crew Chief Zoran Mirić