Orpheus and Eurydice

opera by Christoph Willibald Gluck

CHRISTOPH WILLIBALD GLUCK

(1714 - 1787)

Against his father’s will, who let him only sing and play music in church, young Gluck made his way to Prague supporting himself by modest income earned by playing at dances. Then he set off for Italy to become quite a well-known Italian opera composer. However, after many journeys with travelling Italian opera companies Gluck settled in Vienna for a longer period and becoming impressed by the reform of Italian drama stage, he tried to reform also the opera stage, and instead of set figures and music which was independent of dramatic action, he tried to create a new opera that would express dramatic truth and reality also through music. In his first Viennese opera series he was still unable to find a proper solution for what he had been searching, for more expressive stage music, but with each opera he came closer and closer to that goal. After his triumphant visit to Rome, Calzabigi came to his aid by writing a libretto that enabled Gluck’s music reforms and in 1762 the first reformed opera, Orpheus and Eurydice, was finally completed, followed by another two, in the introduction of which the composer explains his intentions. The battle for a new, reformed opera was mainly fought in Paris between Gluck and the supporters of the then most popular Italian composer, Piccinni. After a difficult struggle, Gluck won, so the Italian opera also accepted his reforms.

Gluck’s genius observed that opera that was based on strictly music concepts could neither achieve real stage and dramatic effects nor express all those emotions, excitement or joy that should be brought out in dramatic effects of a stage play. In that respect, librettos also made it difficult for the music to be the proper expression of dramatic reality, although on drama stage the reform was at full blast. Gluck searched for the tools and means to enhance the events on the stage when it comes to expression of emotions and to closely link music to music drama so that it could become its organic whole. He could not create those types of emotions freely in his texts and put them on the stage, and thus he turned to classical types that generally represent certain characteristics. That enabled him to introduce choir and ballet in the composition of dramatic effects, apart from arias and group singing, and in that way he put the entire stage effect of music drama in the service of stage and dramatic expressions. By doing that he created opera in the current sense of the word, because the music was no longer independent, i.e. not linked to dramatic events and actions, but it became an organic part of the whole, and on the other hand dramatic characters were no longer marionettes but they rather expressed human feelings, temperament and characteristics.

In the development of opera from Monteverdi to Wagner from the initial phase of dramatic and stage music to the so-called “Gesamtkunstwerk”, Gluck was the immediate successor of Monteverdi and created the base for Wagner’s beliefs. His creative work completely corresponded to the development of music and all art branches in the time when art finally abandoned the narrow frame of a privileged social class and became the means for achieving the material and cultural level on which this surviving class was also disappearing.

With his music forms Gluck could not but reform drama music as well, so by remaining faithful to Italian melodiousness, he broke those strict three-part arias and subjected the whole music to dramatic notion, so it could also participate in the entire event on the stage and in the orchestra, whereas light, easy-going melodies linked to fuller harmonies of German music gave a specific character to Gluck’s music.

“ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE”

POETICS OF SIMPLICITY

The opera “Orpheus and Eurydice” is based on the ancient Greek myth about tragic love. Orpheus was a legendary singer and poet, the son of Calliope, one of the Muses. According to the legend, whenever he would play his lyre he got as a gift from Apollo, the god of music, the nature itself could not resist its beauty. His wife, the nymph Eurydice, died of a snake bite soon after they were married. Orpheus was so heart-broken that he decided to go down to the underworld to try to bring her back. The gods of the underworld were so spellbound by Orpheus’ playing the lyre they allowed him to take Eurydice’s soul to the light of day which would bring her back to life, but on condition that he must not look back until they both exit the underworld. Confused and under huge pressure, not recognising Eurydice in the apparition whose movement he felt behind him, he did look back and so for the second and last time lost his loved one. Orpheus and Eurydice were also the main protagonists of the operas written in the early 17th century – Striggio’s Eurydice from 1600 and Monteverdi’s Orpheus from 1607. This piece belongs to the genre azione teatrale, which means an opera with a theme from mythology with choruses and dance. The opera was first performed at the Burgtheater in Vienna on October 5, 1762 in the presence of Empress Maria Theresa. Orpheus and Eurydice was the first of Gluck’s “reformed” operas in which he tried to replace perplexing plots and overly complex music with “noble simplicity” both in the music and the drama. The Essay on the Opera by Francesco Algarotti (1775) had a major influence on Gluck in his development of reformist ideology. Algarotti proposed a very simplified opera model, with an accent on drama, instead on the music or ballet. The drama itself should “delight the eyes and ears, to rouse up and to affect the hearts of an audience”. Algarotti’s ideas had an influence on Gluck and his librettist Calzabigi, who was also a prominent advocate of reforms, who stated: “If Mr Gluck was the creator of dramatic music, he did not create it from nothing. I provided him with the material or the chaos, if you like. We therefore share the honour of that creation”.

This opera is Gluck’s most popular work and it was one of the most influential on all German operas that followed. Variations on its plot – the underworld rescue mission in which the hero must control or conceal his emotions – can be found in Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Beethoven’s Fidelio and Wagner’s The Rhinegold.

In 1769, in a performance for Le feste d’Apollo in Parma, Gluck reworked part of the role of Orpheus for soprano. Although it was originally set to an Italian libretto, Orpheus and Eurydice owes a lot to French opera genre, particularly in its use of accompanied recitative and general absence of vocal virtuosity. Actually, twelve years after the premiere in 1762 Gluck adapted his opera more to the taste of Parisian audience at the Royal Music Academy (Académie Royale de Musique) with a libretto written by Pierre-Louis Moline. Several alterations were made in vocal casting and orchestration to suit French taste. The fourth version, made by Hector Berlioz in 1859, used the original score from Vienna from 1762, including most of the additional music from the Paris score from 1774. He also renewed some more subtle orchestrations from the Italian version and prepared a version of the opera - in four acts - and Orpheus was performed by a mezzo-soprano.

prepared by Jovan Tarbuk

A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR

The act of directing Gluck’s opera Orpheus and Eurydice in the light of Eleusinian mysteries contains four key phenomena that precisely define this opera to be produced at the National Theatre in Belgrade. These phenomena include an innovative opera composer, a revolutionary in the field of synthesis of music and drama, one of the biggest opera reformers in the history of this stage form – Christoph Willibald Gluck, then Orpheus and Eurydice – the central myth from the circle of the Orphic myths that speaks of the artist archetype, of a supreme power of spiritual artistic individual who can change even the implacable laws of life and death to which we all must succumb, followed by Eleusinian mysteries – an ancient mystical cult of pre-classical Greece dedicated to understanding and acceptance of natural and inevitable cycle of life and death, and the fourth, and the last one – a mystery – the thing that cannot be fully comprehended, a secret, a puzzle. Each of those four concepts carries its own value and it represents a wide area for research by itself, however, it is only their interrelations practically embodied in directing the opera that open the door to essentially innovative stage adaptation.

The role of Orpheus, as the central figure of the show, which was originally written for a castrato, is played by a mezzo-soprano – the very choice of this singing voice and gender controversy already indicate a non-standard hero in a macho world who certainly does not use the means of Hercules, Achilles and Ajax. His determination and courage are not contrasted to his gentleness, sensitivity and vulnerability, but they rather make a good counterpoint which triumphs even in domains where masculinity and machoism have no success. His charisma and poetic zeal manage to touch even the relentless chthonic deities who are not malicious but with the great sense of duty care about the higher order in the universe. With his many heroic deeds Orpheus justly deserves the title of a hero, equally with the title of a poet, prophet and a philanthropist of humanity. His strength comes from love which at the same time harbors his greatest mistake through which the myth teaches us that weakness towards the object of our affection is not the same as true love.

Eurydice and Amore are given immeasurably smaller space in the piece and they are both depicted with only a few large brush moves so sufficient space is given to the director’s interpretation to deepen them through further research. Eurydice’s excessive yearning for the world of the living and still vivid memory after drinking the water from the river of oblivion make her restless and ardent which Hellenic and classicist system of value recognize as a fatal character flaw. Despite major proofs of love, the weaknesses of Orpheus and Eurydice can no longer endure Amore’s hardest tests. Still, Orpheus’ decision to sacrifice the most valuable thing (his own life) redeems both lovers in the eyes of the god. Amore, unlike Orpheus and Eurydice, possesses in his expression the most interesting Gluck’s director-composer’s innovation which is a music subtext opposite to verbal text. Although he speaks sentences that, without music, could be interpreted as cruel orders, the parallel music material which is frivolous, charming and humorous tells us that this is a seductive and flirting deity, persistent, benevolent and childishly irresistible, although overbearing and dominant.

The mysteriousness and fathomlessness of certain concepts surpass our everyday banal existence, and the spheres to which our comprehension can reach regardless of the fact that our education and access to information made us took for granted that the Earth is a ball kept by gravity at a certain distance from the Sun or that a water molecule contains an atom of oxygen and two atoms of hydrogen. Mystic forces spoke to our ancestors in a much deeper and significant way about the secrets of birth and death. “Poetic and mystical truth” may have been much more true to our ancestor than our “truth of science and ratio”, and if not more true than certainly more important for his spiritual life and spiritual survival. Though almost all medical disciplines (from those focused on our physical health to those concerned with our mental health) directly or indirectly serve to prevent, postpone or deal with the consequences of death, to a modern man they do not provide solace and profound understanding of the cycle of life, breeding and death that our ancestors (perhaps) used to comprehend with much more composure. Modern fears, neurosis and phobias which are the reflection of an unhealthy attitude towards death are the real image of Western civilization resting on egocentricity, highly developed individualism and confidence in the achievements of human ratio, although many secrets of life and death surpass it despite the rapid progress of science in all fields. Discomfort, fear, revolt, lack of understanding, anger, sorrow, depression, feeling of purposelessness, of being lost, helpless are what millions of people around the world feel on a daily basis who confront death directly or indirectly – such dreadful existence represents everyday life of a modern man in general, who is neither under the protection of god (or gods) nor can he use his powers to save himself from this great and terrifying mystery.

Hades’ and Persephone’s secrets remain locked for us, the 21st century people, unless we express them through artistic form, and in our specific case through musical theatre. How else can we cope with such decisive and fathomless themes of our existence than through the medium that uses music, words, poetry, colour, light and darkness, movement, composition, rhythm, contrast, story, drama, acting, and above all a real live man as an instrument…thus mesmerizing all our senses and preparing them for enlightenment beyond the banality of everyday life.

Aleksandar Nikolić

SYNOPSIS

Act 1. “A pleasant but secluded grove of laurel and cypress trees which encloses, in a clearing, the tomb of Eurydice on a small dais. As the curtain rises to the sound of a mournful symphony, the stage is occupied by a group of shepherds and nymphs, followers of Orpheus, carrying wreaths of flowers and garlands of myrtle: while some of them adorn the marble and strew flowers round the tomb, the others sing the following chorus, interrupted by the laments of Orpheus who, lying prostrate on a rock, from time to time passionately repeats the name of Eurydice” (original Calzabigi’s stage direction). Orpheus interrupts this sad song and sees his friends off; he wants to be alone with his grief.

After contemplating on the misfortune that fell upon him and sharing with them the reason for his lament, the singer from Thrace openly challenges the gods by telling them that he is ready to descend to the Underworld to find his wife, without whom he cannot live. Amore appears, who speaks on behalf of Jupiter: the master of Mt Olympus showed mercy and let Orpheus cross the river Lethe alive. If he succeeds to warm up the gods of the Underworld with his song, he will be able to bring back Eurydice. However, he must fulfil one condition to get this task done: he must neither look back at his wife nor must he tell her about this condition, until they have both completely exited the Underworld. If he should disobey, he will lose Eurydice again, this time for good. Realising how hard it would be for him to fulfil this condition, Orpheus hurries to complete this bold quest.

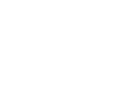

Act 2. Scene one. “A fearsome cavernous region beyond the river Cocytus, darkened from afar by gloomy smoke lit up by flames which envelops that whole dreaded abode. As soon as the scene is changed, with the sound of horrific symphony, the dance of Furies and spectres begins interrupted by the harmonious sound of Orpheus’ lyre. The entire infernal crowd starts singing in chorus.” Angered gods of the Underworld try to prevent the passage of the fearless mortal, who dared go “in the footsteps of Hercules and Pirithous”, but Orpheus slowly calms them with his sad song and the sound of lyre. At the end, “The Furies and monsters begin to withdraw, and as they disperse from the stage they repeat the last strophe of the chorus, which continues until they finally disappear. When they have gone, Orpheus advances into the infernal regions”.

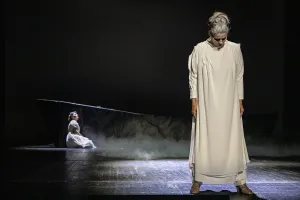

Scene two. “A delightful region with verdant groves and flower filled meadows, extensive shady spots, and rivers and streams flowing through it.” Orpheus, arriving at the Elysian fields, looks at this surreal beauty that surrounds him with a thrilling sensation. He goes towards the blissful spirits who sing and dance; Eurydice is led by a Chorus of heroines towards Orpheus, who, without looking at her, takes her by the hand and quickly leads her away. Then follows the dance of heroes and heroines, and the Chorus resumes its chant, which should continue until Orpheus and Eurydice are in fact outside the Elysian Fields.”

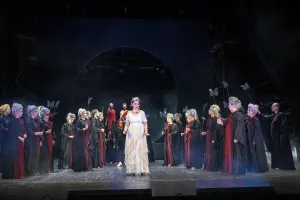

Act 3. Scene one. A dark cave that forms a tortuous labyrinth, obstructed by boulders separated by rocks completely covered with brushwood and wild plants.” Orpheus hurries to leave this underworld realm, leading Eurydice by the hand all the time, without looking back at her. After the initial surprise, brought back to life, she starts harassing her husband with questions: how and by what art she managed to come to the light of day. And why Orpheus is in such a hurry and agitated that he did not even look at her. Bound by the divine prohibition, the singer avoids directly answering her questions, thus only increasing her female discontent. Becoming more and more bitter by Orpheus’ behaviour, which astounds her, she provokes a bitter argument with fatal consequences: desperate, Orpheus finally looks back at Eurydice and she instantly takes her last breath collapsing at his feet. Divine law has been broken and he lost Eurydice for good. Calling his wife’s name, Orpheus decides to join her forever by killing himself. Yet, once again Amore interferes: the gods, deeply shaken by such tremendous love, annul the law. Eurydice will rise to be reunited with her Orpheus.

Scene two. “A magnificent temple dedicated to Love. Amor, Orpheus and Eurydice, preceded by a large number of shepherds and shepherdesses, who have come to celebrate Eurydice’s return and begin a lively dance.”

Premiere performance

Libretto: Ranieri de’ Calzabigi

Conductor: Dian Tchobanov, guest artist / Zorica Mitev Vojnović

Director: Aleksandar Nikolić

Set Designer: Dunja Kostić

Costume Designer: Katarina Grčić Nikolić

Coreographer: Aleksandar Ilić

Cast:

ORPHEО: Aleksandra Angelov, Jana Cvetković*, Ljubica Vraneš

EURIDICE: Snežana Savičić Sekulić, Nevena Bridgen, Marija Jelić*, Isidora Stevanović*

AMORE: Sofija Pižurica, Ivanka Raković Krstonošić, Milica Damjanac*, Nevena Đoković*

SOULS IN PURGATORY, SOULS IN HELL, SOULS IN HEAVEN, FOLLOWERS OF ORPHEUS: Choir

PERSEPHONE: Iva Ignjatović

MORPHEUS, FURY: Dragana Nedić

CERBERUS, FURY: Sanja Tomić, Ines Ivković, Jelena Momirov, Jelena Nedić

CUPID, FURY: Ana Ivančević, Ljupka Stamenovski, Anastasia Sihova

MOIRA: Nada Stamatović, Željko Grozdanović, Gordana Jeličić

SOUL OF EURIDICE: Milena Stajkić

*A student of opera studio „Borislav Popović“

WITH PARTICIPATION OF CHOIR, ORCHESTRA AND BALLET OF THE NATIONAL THEATRE IN BELGRADE

Concertmaster: Edit Makedonska/Dina Bobić (deputy concertmaster)

Chorus Master: Đorđe Stanković

Assistant conductor, expert associate: Predrag Gosta

Executive producer: Milorad Jovanović

Producer: Maša Milanović Minić

Harpsichord: Predrag Gosta, Nevena Živković, Nada Matijević, Gleb Gorbunov

Subtitles libretto translation: Maja Janušić

Music Reherseal Associates: Srđan Jaraković, Nevena Živković, Nada Matijević, Gleb Gorbunov

Stage Manager: Ana Milićević/Dejan Filipović

Prompter: Dijana Cvetković

Light Design: Milan Kolarević

Make-Up: Marko Dukić

Stage Crew Chief: Nevenko Radanović

Sound Operater: Tihomir Savić

Video: Petar Antonović

Extras led by Zoran Trifunović

Costumes and sets were manufactured in the National Theatre workshops.