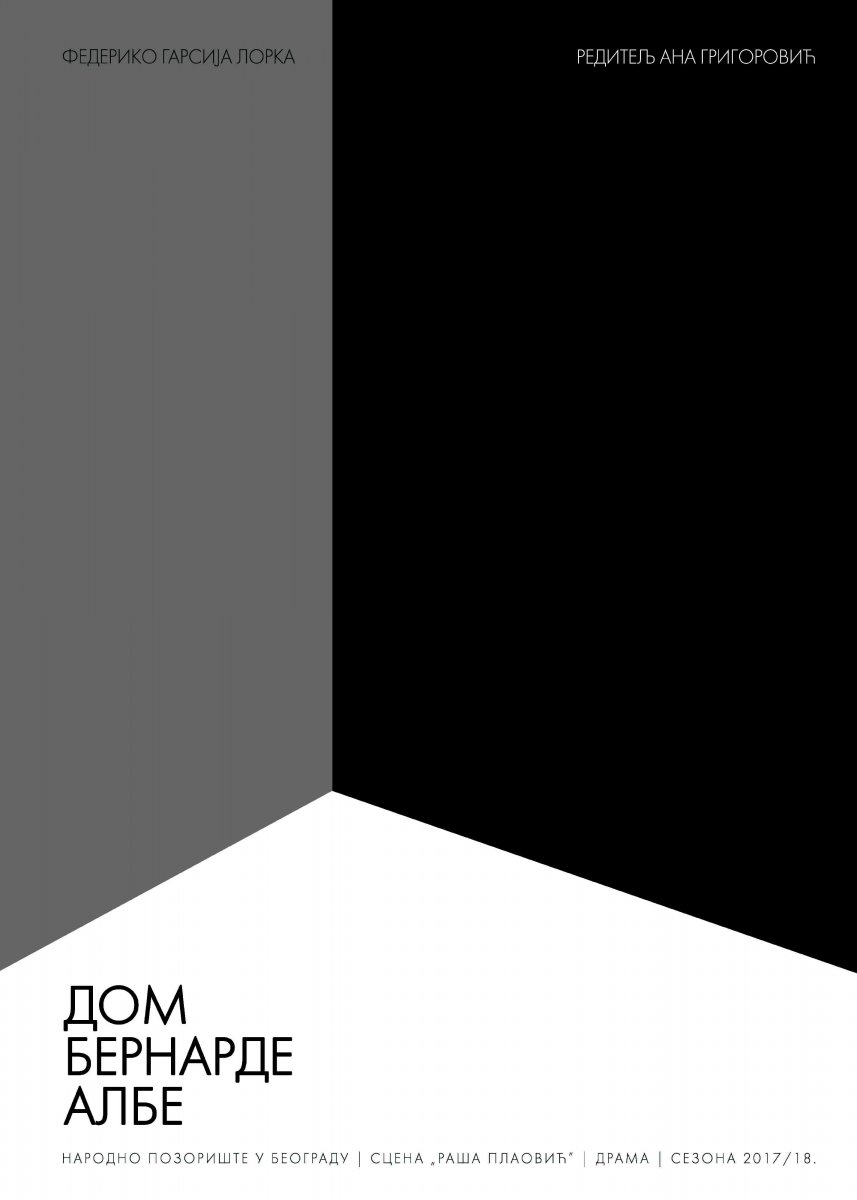

The house of Bernarda Alba

drama by Federico Garcia Lorca

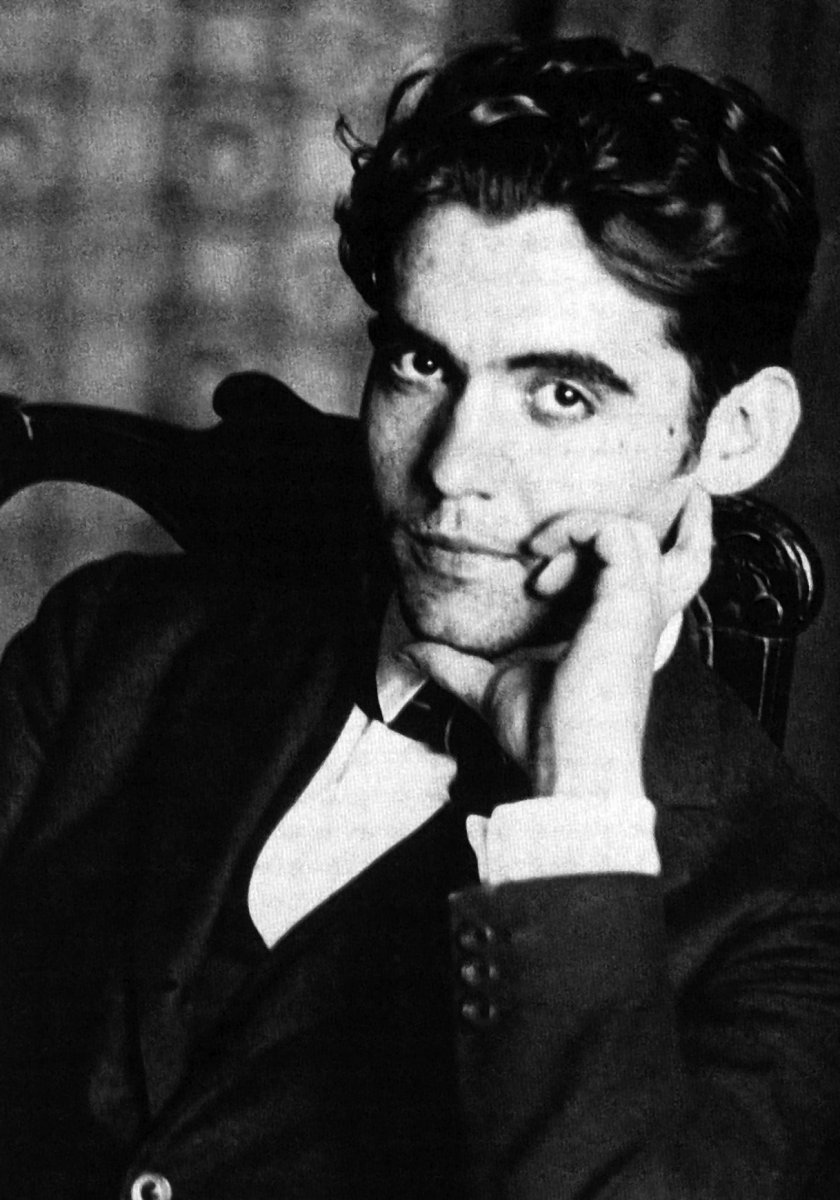

RUMOURS ABOUT FEDERICO GARCIA LORCA

Alongside Cervantes, Federico Garcia Lorca is the most universal Spanish writer and primarily an authentic symbol of Spanish culture. His works encompass folk song form, but also the universal, cosmopolitan, traditional and, of course, the avant-garde, which all together make the recognizable profi le of Spanish distinctiveness. Actually, it is the liveliest attribute in understanding one’s own existence within the abundance of traces brought together in a garland made of passion, love, pain and dreams. In Lorca’s work everything reached to comprehensiveness because he simultaneously went together with the time and before it, in order to explore, discover, explain and interpret what is hidden in layers of time and soul, history and present, while he painted freedom with his imagination and symbols as a divine inspiration and poetic escape from imposed limits, deeply and sincerely believing in his predetermined destiny of a poet.

Jordan Jelić, He Died at Daybreak

Federico Garcia Lorca is a hero of the Spanish Civil War, a poet of a nation and an idea understood in the most pathetic and romantic sense of the word. Lorca belongs to the group of writers who due to their idiosyncrasy definitely escape any literary systematization. The most we can say about his plays is that they belong to poetic drama, but as soon as we state that, we feel the need to define more closely the poetics of his plays and his dramaturgy in general. Language in Lorca’s plays develops from rhythmical prose and rhythmical verse in his early works (Yerma, Blood Wedding) to prose structure in his last play, The House of Bernarda Alba. Nonetheless, regardless if he writes prose or verse, Lorca, as a poet of extraordinary imagination and sensibility, creates a drama language that adequately expresses abundance of passion of Andalusian blood. Three of his most important plays, tragedy Blood Wedding, Yerma and The House of Bernarda Alba, possess similar themes. In the three plays, women have either exclusive or the most important parts, while male characters are more or less there as objects of their forbidden passion, restlessness, fears or mourning. In addition, in the three plays, death is a dark shadow overcastting all events and also, in these plays, rigorous traditions and moral are in conflict with volcanic passions of heroes, thus causing tragic endings.

Slobodan Selenić, Drama Movements in XX Century, Belgrade, 2002

At the time of his slaying, Lorca was thirty-eight. With the publication of Gypsy Ballads, composed while he was still in his twenties, he had become, almost instantly, Spain’s most famous poet, and the phenomenal success of his Andalusian tragedies Blood Wedding and Yerma had made him the country’s most celebrated dramatist as well. From early childhood, Lorca had been obsessed with his own death, including the details of his interment. Salvador Dali, a close friend and, probably, love interest, recalled how Lorca, as a student in Madrid, used to act out his burial, describing the position of the corpse, the closing of the coffin, and the bumpy passage of the funeral procession over the cobbled streets. During the Spanish Civil War, thousands of people were buried in unmarked mass graves, and opening of those graves is being perpetually hindered by political reasons. Lorca became a symbol of search for truth, although his remains have never been found. “There were thousands of versions, people often boast and claim that they know something that they do not know,” stated Gibson. “One evening, they tell you one thing, but the next, they tell you something completely different.” Gibson published the results of his investigation, titled The Death of Lorca, in 1971. One of the most striking claims in Gibson’s book is that Lorca could have actually avoided his execution. There were many strikes, street violence and assassinations of high officials in the period of several weeks before the coup that led to civil war; it was clear that republican government was struggling. Lorca was desperate and did not know what to do. Contrary to advice of his colleagues, he decided to leave Madrid, where he lived, and go to Granada, which he did on 13th July, only four days prior to Franco’s coup. Before leaving, he told a friend, “It’s in God’s hands.” Within a week, Granada fell into the hands of nationalists, while Madrid remained republican until the end of the war. Lorca’s left-wing views were well known throughout Spain. His tragedies, although not openly political, could be interpreted as a criticism of oppressive nature of Spanish society. “I will always be on the side of those who have nothing and who are not even allowed to enjoy the nothing they have in peace”, said Lorca. However, Lorca refused joining any party and claimed that his life and work are outside any ideology. “I will never be political,” he told a friend in Madrid, just before the war broke out, “I am a revolutionary because there are no true poets that are not revolutionaries. Don’t you agree? But political, I will never, never be!”

Elizabeth Kolbert, Letter from Spain, Looking for Lorca, 1971

ANA GRIGOROVIĆ

ANA GRIGOROVIĆ

Ana Grigorović was born in Belgrade in 1987. She graduated from the Department of Theatre and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Drama Arts, mentored by Professor Ivana Vujić. In addition, she obtained her interdisciplinary Master’s Degree in Theory of Arts and Media at the University of Arts in Belgrade. She stage directed the following productions: Magic Afternoon (W. Bauer, Atelier 212), Gianni Schicchi (G. Puccini, National Theatre in Belgrade), Bastien and Bastienne (W. A. Mozart, National Theatre in Belgrade), Play (S. Beckett, Theatre “Bora Stanković”, Vranje), The Feast (Plato, Bitef Theatre), The Birth of a Record (B. Pekić, National Theatre Pirot), To Be (V. Nikolić, Institution of Culture “Parobrod), Peter (Ž. Hubač, Bitef Theatre), National Class (G. Marković, Youth Theatre “Dadov”), Fifty Strokes (T. Baračkov, Atelier 212), Five Boys (S. Semenič, Little Theatre “Duško Radović”), If I Want to Whistle, I Whistle (A. Valean, National Theatre “Sterija”, Vršac), Beauty and the Beast (Ž. Hubač, Theatre “Bora Stanković”, Vranje), The Escape (E. Ionesco, Institution of Culture “Vuk Karadžić”), The Paul Street Boys (F. Molnar, Youth Theatre “Dadov”), North For¬ce (M. Bogavac, Youth Theatre “Dadov”), After Sun (Rodrigo Garcia, Student Cultural Centre Belgrade) Grigorović won the “Hugo Klajn” Award for Best in Class at the Department of Stage Directing in her generation; “Zoran Ratković“ Award for Stage Directing; the City of Belgrade Award in category of Young People’s Accomplishments in the Sphere of Art in 2009; the National Theatre’s Award for Best Performance in 2016/17 season and the Recognition of the National Theatre for stage directing of opera Gianni Schicchi.

SILENCE!

Lorca found the inspiration and source for his play The House of Bernarda Alba in a well. Our basis for staging of the play is a window. It is a kitchen window, which opens to the hall of the building, just like all other kitchen windows of other families who live there, who argue, love, hate, cry or fight inside. And, everything can be heard. And, everybody knows that. If strong emotions and passions take over, while the window is open, one can hear a lot, everything, maybe too much. This is why one sometimes stands behind the window and listens in. However, more often than that, one moves away or hushes somebody from it.

Silence!

The first and last line spoken by Bernarda in the play is, “Silence”. In the beginning, it is a warning for establishing interactions within the house, and in the end, it is a sign of establishing relationship with people listening in from the outside. The starting point of this interpretation of The House of Bernarda Alba is this striving for silence and constant inability to create it. What does the silence mean? Why is it important? After the death of her husband, Bernarda becomes the head of the house. Such position imposes on her the responsibility and the task of maintaining piece, order and honour, just like a man. This objective results from moral and religious rules she is guided by; however, it is only on the surface. Bernarda’s care for her daughters and her need to have everything under control is the result of her fear of what will the world, i.e. the village, think and say about her. Guided by this fear, she tries to save the honour of her family, to keep their reputations intact, but with her fear from gossiping she actually destroys what she is trying to protect. Poncia is the only one in the house who represents the society; Bernarda takes her as the orientation point while setting her principles. This is why their relationship is in constant shift from being on friendly terms to being in a conflict, in constant change of roles and games of power. Poncia is the only one who notices the daughters’ emotions, their needs and desires, but she is not a surrogate mother for Bernarda’s daughters, she cannot be one, because she has to observe the established social conventions of their society. A society that rules by means of violence and fear, where good people, led by tyrannical principles, become mean. This is why Poncia is there only to listen, to serve and, occasionally, reveal the joys of life and forbidden emotions to the daughters. Contrary to this, Bernarda’s relationship with her daughters is deprived of emotions. To her, their behaviour is more important than their feelings. This attitude is revealed by her frantic wish to maintain dignity and honour of the family. The wish overwhelms Bernarda and turns into violence. For her daughters’ sake, she terrorizes them, thus creating new cruelty, which inevitably leads to disaster. Bernarda protects and hides her daughters from the world; the world that we never see, we just hear it. The sound is not merely the issue of atmosphere, it is the background noise of the world outside the house, the world inaccessible and forbidden to the daughters, which causes their desire to become greater and more insufferable. The men in the play do not appear physically, they are constantly present through the means of voice, song, shouting; villagers chasing Librada’s daughter to punish her, harvesters going to the fields and finally, Pepe whose whistle announces disaster. The play is set in the unbearable heat of an extremely hot summer. It fuels the passions in the daughters. The sexuality is strictly forbidden, it was suppressed even before it could show, which made it even more dangerous. Bernarda is aware of the dangers of passion; this is why she is so determined to prevent her daughters from expressing them in such an autocratic manner. Suppressed emotions regarding sexuality create complete lack of emotions, this is why we observe atmosphere full of bitterness and hate among the sisters. However, Pepe is not the object of their conflict; it is not him that they want. He is only the cause. They all want to fulfil their deepest natural needs, to prevail over the imposed silence. The sexuality they never speak about, which is under no circumstances expressed or seen, cannot remain hidden in silence. One can close the windows to the world outside and one can force their daughters to stay inside, to wear mourning clothes and not to cry, but one cannot triumph over the inner fires. This is why feminine passions and sexuality, although almost imperceptible and quiet in the beginning, became the loudest in the end, they scream to such an extent that they result in tragedy. This is precisely why the silence is not pleasant and natural; instead, it is a suppressed scream, which, at a certain point, must be expressed, thus inevitably leading into death.

Vanja Nikolić

Premiere performance

Premiere, 5th April 2018 / „Raša Plaović Stage

Stage Director Ana Grigorović

Dramaturgy and Text Adaptation Vanja Nikolić

Set Designer Marija Jevtić

Costume Designer Katarina Grčić Nikolić

Language Editor Dr Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Composer Maja Bosnić

Sound Designer Dragan Stevanović Bagzi

Stage Movement Associate Tamara Antonijević

Executive Producer Vuk Miletić

Producer Nemanja Konstantinović

Premiere Cast:

Bernarda Dara Džokić

Poncia Svetlana Bojković

Angustias Zlatija Ocokoljić Ivanović

Magdalena Dubravka Kovjanić

Amelia Zorana Bećić

Martirio Sloboda Mićalović

Adela Suzana Lukić

Maria Josefa (voice) Rada Đuričin

Girl Sara Vuksanović*

Producerin training Milica Tatomirović

Stage Manager Sanja Ugrinić Mimica

Prompter Dušanka Vukić

Assistant Stage Director Nevena Mijatović

Assistant Costume Designer Aleksandra Pecić

Assistant Set Designer Dunja Kostić

Light Operater Miodrag Milivojević

Make-Up Marko Dukić

Stage Crew Chief Zoran Mirić

Sound Operater Roko Mimica

SETS AND COSTUMES WERE MANUFACTURED IN THE NATIONAL THEATRE WORKSHOPS

*Student of Primary School Danilo Kiš in Belgrade