Caligula

drama by Alber Camus

.jpg)

ALBERT CAMUS

ALBERT CAMUS

Albert Camus (Mondovi, Algeria, 7.11.1913 - Villeblevin, 4.1.1960), French philosophical writer, engaged intellectual; winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature (1957). His childhood in Algeria without a father who died in World War I in 1914 in the famous Battle of the Marne, with a mother who worked painstakingly to raise him - was marked by scarcity and pain. Nevertheless, remembering his childhood and homeland, Camus wrote: I was born poor but happy, in harmony with nature. So, I did not start life with strife but with fullness. He was educated under difficult conditions, doing various jobs to support himself (merchant, traveler, meteorologist, clerk ...). At the same time, he was passionate about football, journalism and theater; He founded the troupe “Team” L ‘Equipe) for which he writes, directs and plays. At the beginning of the world war II, he volunteered but was rejected for tuberculosis. He joined the resistance movement in 1942, publishing at the same time his novel The Stranger, which had great success; At the end of the war he became the editor-in-chief of Le combat. He developed the idea of the absurd (symbolism of the myth of Sisyphus) and the idea of revolt (symbolic of the Prometheus myth). Charachters from the cycle of the absurd: the novel The Stranger (1942), the dramas Misunderstanding (1944), and Caligula (1945) are “eaten away by the aimlessness, uselessness of life, split between the indifference of the universe and the hypocrisy of a society whose moral values are based on lies. But, as there is no other world, such characters are left to automatism that inexorably leads to individualism, crime, breakup or madness. “Yet, in the novel Plague (1947) and the essay The Rebel Man, Camus distances himself from Sartre’s existentialist nihilism and advocates for the positive values of human solidarity in response to the absurdity of the world, violence and suffering; in these works he emphasizes compassion, mercy, truth, honesty. Camus’s personality traits from a young age - enthusiasm, impatience, grand plans, remain a lasting seal; that elan, is a lasting characteristic of his personality. Camus remained in the memories: intoxicated by life, on the move, smiling, full of interest in all things happening, people, football, jazz ...

In addition, his other works are: The Myth of Sisyphus; essays in collections entitled Summer, Letters to a German Friend, Novel Pad; dramas, The Righteous, The Siege, and more.

(From: Encyclopedia of Enlightenment; Croatian Encyclopedia, M. Krleža Lexicographic Institute ;, SNP Encyclopedia; Albert Camus, N. Marinkovic)

ABOUT CAMUS

Theatre Tendencies in the 20th Century,

Slobodan Selenić

A type of play, which is possible to be named philosophical, has been observed as a special type of theatrical creation which can be singled out from the colourful background naturally created by the dramaturgy of the XX century; it is a play which takes basic principles of a philosophy, which is hypothetical for the play, and turns them into characters and situations in the play. The characters in this type of play are not free in the sense they are in realistic dramaturgy; their actions are not psychologically motivated. The situations, as well, are not consequences of action, instead, all elements of drama, all conflicts, all resolutions – are determined by premises of the philosophy which is hypothetical for the play. Drama is an illustration of beliefs which precede creation of the drama.

“There were no psychological reasons that brought Camus’s Caligula to a state in which he does despicable things, it was his philosophical belief that each and every action is equally absurd in this absurd world – an action that complies with the norms of civilised behaviour and the one that sees murder as a legitimate act that does not ask for justification and reasons”.

“Caligula is a young Roman Emperor who, at the same time when he comes to power, comes to realisation vis-à-vis the absurdity of life. This simple but indisputable truth about the world is not known to Roman patricians who came up with numerous obstacles in order not to be able to see the final absurdity of the world. Caligula decides to force patricians to see the absurdity of the world and he wants to achieve that by performing absurd activities which would actually be no more absurd than the absurdity that rules the universe. He kills for no reason, he rapes women, he proclaims his horse a senator, he closes the granaries and condemns the people to hunger – his intention is to ridicule moral values, integrity and faith in logic on which the selfdeception of patricians lie.“

Germaine Bree in her book on Camus notices that his plays are arranged in such a way that one of the characters instigates plot within the plot on stage. The situation in Caligula has been created by Camus, but Caligula himself orchestrates action, a sort of a play within the play, in order to show the patricians the stupidity of their blindness regarding the fact that human universe is absurd. (…) Those instigators of action, appear, according to Jacques Guicharnaud’s definition, as “tyrants, liberators and experiment takers” and this typology has been almost completely followed in all plays of the “theatre of situations”, therefore one could use the typology to define whether a play belongs to this style (…) Caligula is one of the experiment takers. The three categories of people who try to bring their order to the world are a metaphor for oppressive order of the universe and behaviour of a free man who needs to find his place in it – it is a basic pattern which achieves engagement of these plays.

NIHILISTIC UTOPIA - A NOTE BY THE DRAMATURGE

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, nicknamed Caligula, was a Roman emperor in the first century AD. As a favourite son of a popular general Germanicus, Caligula started his reign in peace and overall bliss. However, upon an early illness or a possible case of poisoning, he altered the style of his reign, thus his contemporaries describe him as a tyrant, who remained in collective memory as a murderous ruler dedicated to expand his power, regardless of some progressive reforms he implemented. Getting acquainted with historic sources on which Albert Camus based his play cannot hurt, but it is important to remember that Camus’s Caligula is not a historic play, and that any reading which would be based exclusively on history would simply be incorrect. Camus started writing the play in 1938; the first version was published in France right before the end of the Second World War, the war which did not merely bring new technique to kill people. The ideology that inspired the war was so strong in Germany that one could describe it as a sort of a nihilistic utopia. An event that can illustrate the passion of the ideology happened in the Sportpalast arena in Berlin on 18th February 1943, when Germans, together with Joseph Goebbels, fervently chanted for total war until overall (self)destruction, although it had started to become obvious that Germany would be defeated in time. How can one understand the German people’s passion to continue with atrocities and go towards ruin?

Several years ago, I visited Majdanek, a concentration camp from the Second World War near Lublin in Poland. Due to its proximity to the border with Soviet Union and the fact that the Germans had to leave it in haste at the end of the War, Majdanek remains one of the best preserved remnants of Nazi barbarism. I went there expecting to see evil, hatred, affect… instead, I found logic. Terrible, evil, monstrous, yes, but nonetheless - logic. And that shocked me, more than the mountain of bones next to crematorium, or warehouses full of civilian shoes left behind the victims, or the other terrifying artefacts in the museum – therefore, it was not hatred, it was opposite, the lack of hatred, the lack of emotion, that stunned me. What I found in Majdanek was not a place of crime, it was industry of death and its terrifying precision and pragmatism, an industry that served for no other purpose than to produce a terrible testimonial of its own arbitrary action. Jews were not people and it was necessary to eradicate them because the Germans decided so at a certain point – and the freedom to make such a decision was exactly what made them Germans in that point in history.

There are readings of the play and productions that view Camus’s play primarily in light of horrors that the world went through by introduction of new, illicit ideologies and absurd fanaticism of their followers. Although such (let’s call them ‘political’) readings could be inspirational as well, I believe that they are not ambitious enough for a play such as Caligula. Even if we start thinking about the play from the perspective of concentration camps as the end of European civilization, the question I would like to have answered is not merely what kind of person was the ‘insane’ Leader who ordered creation of the camps, but primarily how did the introduction of the camps into political (ethical) sphere changed us as people. Us, today. The Nazi leader is gone, but the logic I found in Majdanek still exists. Today, more than ever before, we worship individuals who give themselves the fantastic and charismatic freedom not to be human, regardless if they are in the sphere of culture, politics or economy – those who break boring rules of society, for which we all know very well that do not exist anymore, regardless of how well we pretend not to. We worship creativity, functionality, capability to get things done even if it means overlooking hundreds of thousands of deaths for increase in a profit margin for a few percent; this became such a norm that any CEO who wold allow his company to suffer financially, merely because of safety of some peasants on the other end of the world, would immediately be let go. The reading which is opened in this manner puts Caligula down from safe heights (for us) of emperors, chancellors and leaders, and places him in a modest place of a Contemporary subject. In your or my place – a place of free, thinking men who, although they may believe in God, have the faith based on tradition and culture more than on radical universal emancipatory or ethic requirements. The unpleasant question we face while reading Caligula by Camus is whether there is a straight line leading to concentration camps from the point in history when bourgeois society was born, when the men were freed during the renaissance and when the God died. Can we imagine some other universal project or is there no place for another utopia – the one focused on life, in the nihilistic utopia in which we live?

Milan Marković Matthis

A WORD BY THE DIRECTOR – AGONY OF ABSURD

The beginning of 21st century is abundant with knowledge and information regarding the crisis of the world order, as well as that the pinnacle of our civilisation based on neoliberal capitalism is actually a crime against humanity. Numerous hypotheses regarding democracy, social justice and economy have been questioned. Dominant feeling is that the world is not right and that it is quite unrealistic to attempt to change it, therefore the absurd is today a phenomenon which gives the most accurate definition of agony and crisis of an individual.

In his play Caligula, Albert Camus initiates the most pertinent questions regarding the position of man and purpose of life, the possibility of revolution, social and political development and the collapse of society, the idea of freedom, idol worshipping, importance and possibilities of high art and culture in concepts and limitations of the modern world. Camus’s Caligula, the way I interpret it, examines personal possibilities and limitations of social conventions by looking for an exit from the nonsensical world in which religious, moral and political verticals have been collapsed or abused. He plays with known patterns of autocratic rule, tyranny, sociopathic absolutism, idol worshipping in dictatorship and ruthlessly, without compromise and with self-irony, vivisects the whole society by examining positions of an individual, group and the whole structure of the system, politics and power. Caligula brings down ethic norms, social and political patterns and conventions because they are rotten and dishonest. The idea and style of the play provide for a majestic and comprehensive manner to observe, through the prism of the philosophy of absurd, the poetic destruction of soul’s depths, the magic of passion, the tragedy of love, the dark and absurd structure of politics and the idol worshipping fascination.

Camus created a singular and authentic antihero who broadcasts his philosophy of absurd. The reading of Caligula cannot exist without Sisyphus or Meursault. The political revolt in the play creates sort of a false plot which disguises the underground plot. With his behaviour, Caligula inspires the upheaval, the insurgents delay the rebellion while waiting for the right and safe moment. The paradox reveals Camus’s focus on freedom, revolution, purpose of life, suicide. Leader similar to Camus’s Caligula does not exist today. He can assume faces and hidden faces of numerous rulers in order to use them in his tactics as certain principles of political power at the moment, as guidance and as a playing field, but he himself is far beyond these. In search for a much deeper truth, by looking for answers for the purpose and reason to live, he gets closer to death. The antihero of a waning civilization shall dance his last dance. I see this staging as an eerie experiment examining a disappearing world and an individual who has to attempt to establish himself.

Snežana Trišić

THE NATURE OF CALIGULA’S LIFE

As often as he kissed the neck of his wife or mistress, he would say, “So beautiful a throat must be cut whenever I please;” and now and then he would threaten to put his dear Caesonia to the torture, that he might discover why he loved her so passionately.

At a sumptuous entertainment, he fell suddenly into a violent fit of laughter, and upon the consuls, who reclined next to him, respectfully asked him the occasion, “Nothing,” replied he, “but that, upon a single nod of mine, you might both have your throats cut. In the devices of his profuse expenditure, he surpassed all the prodigals that ever lived; inventing a new kind of bath, with strange dishes and suppers, washing in precious unguents, both warm and cold, drinking pearls of immense value dissolved in vinegar, and serving up for his guests loaves and other victuals modelled in gold; often saying, “that a man ought either to be a good economist or an emperor.” He also zealously applied himself to the practice of several other arts of different kinds. He practiced with the weapons used in war; and drove the chariot in circuses built in several places. He was so extremely fond of singing and dancing, that he could not refrain in the theatre from singing with the tragedians, and imitating the gestures of the actors, either by way of applause or correction. A night exhibition which he had ordered the day he was slain, was thought to be intended for no other reason, than to take the opportunity afforded by the licentiousness of the season, to make his first appearance upon the stage.

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

Snežana Trišić graduated from the Department of Theatre and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade in 2009, mentored by Professors Nikola Jevtić and Alisa Stojanović. In period between 2013 and 2015, she worked as a Stage Director in the National Theatre in Subotica. Since 2015, she has been working as an Assistant Professor, and then as a Docent at the Department of Stage Directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, in cooperation with Professor Ivana Vujić. She is enrolled in the third year of her Doctoral Studies of Drama and Audio-Visual Arts at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, mentored by Professor Emeritus Svetozar Rapajić. As a recipient of KENNEDY SCHOLARSHIP (John F. Ken¬nedy Cen¬ter for the Per¬for¬ming Arts, U.S. Sta¬te Department), she participated in the program for stage directors and in numerous workshops, seminars and conferences in Washington D.C., New York and Chicago in 2010. In 2015, Snežana attended the International Seminar for Stage Directors, organised by ASSITEJ Germany in cooperation of ASSITEJ International, in the Schnawwl Theatre in Mannheim, which is a branch of the Mannheim National Theatre, one of the four national theatres in Germany. She has been a member of the Sterijino Pozorje Festival Arts Council since November 2017. Selection of her productions: A Party for Boris, Thomas Bernhard, Prešern Theatre Kranj (2019); Animals, Uglješa Šajtinac, Kruševac Theatre (2018); Moby Dick, Herman Melville / dramatization by Dimitrije Kokanov, Duško Radović Little Theatre (2017); Richard III, William Shakespeare, National Theatre in Belgrade (2017); The Children of Joy, Milena Marković, Atelier 212 Theatre (2016); The Gorge, Žanina Mirčevska, National Theatre Kikinda (2016); Terrorism, Vladimir and Oleg Presnyakov, Belgrade Drama Theatre (2016); What Happened after Nora Left Her Husband; or Pillars of Society, Elfriede Jelinek, Yugoslav Drama Theatre (2015); Kasimir and Karoline, Odon von Horvath, Atelier 212 Theatre (2014); Rhinoceros, Eugene Ionesco, National Theatre Kikinda (2014); Mr. Dollar, Branislav Nušić, National Theatre in Subotica (2014); Bizarre, Željko Hubač, National Theatre in Belgrade / Šabac Theatre (2013); Pinocchio, Carlo Collodi / dramatized by Jelena Mijović, City Theatre Podgorica (2013); The National Drama, Olga Dimitrijević, Bora Stanković Theatre in Vranje (2012); A Miracle in The Viper’s Sweetheart, Ante Tomić / dramatization by Maja Pelević, National Theatre in Subotica (2012); How Much is Pate?, Tanja Šljivar, Atelier 212 Theatre (2012); Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen, National Theatre in Belgrade (2011); Samoudica, Aleksandar Radivojević, Atelier 212 Theatre (2009); The Class, Matjaž Zupančić, National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka (2009). Snežana Trišić won numerous awards and recognitions for directing at the most significant festivals in the country (Yugoslav Theatre Festival, Užice; Festival of Classics, Vršac; Festival of Professional Theatres from Vojvodina; Festival of Professional Theatres of Serbia “Joakim Vujić”; “Days of Comedy” Festival, Jagodina; JoakimInterFest, Kragujevac; Festival “Theatre in Single Action”, Mladenovac, etc.) and abroad (Kotor Children’s Theatre Festival; International Student Theatre Festival in Brno, Czech Republic). For her staging of Kasimir and Karoline, she won the Sterija Award for Directing and Award for Best Play (2015). She was also awarded with recognitions for directing “Ljubomir Muci Draškić” from Atelier 212 Thatre and the City of Belgrade (2009), as well as the “Dr Hugo Klein” Award as the best student of stage directing of her generation, Faculty of Dramatic Arts, Belgrade (2007).

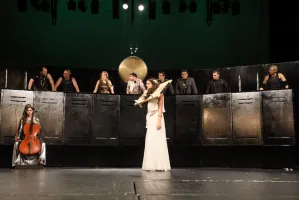

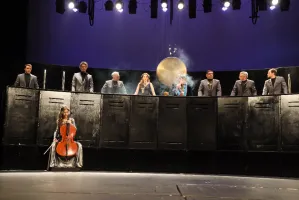

Premiere performance

Premiere 5th february 2020/Main stage

Director Snežana Trišić

Adaptation and Dramaturgy Milan Marković Matthis

Set Design Darko Nedeljković

Costume Design Marina Medenica

Composer Irena Popović Dragović

Choreography/Stage Movement Isidora Stanišić

Stage Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Executive Producer Nemanja Konstantinović

Producer in the Drama Department Miloš Golubović

Stage Manager Sanja Ugrinić Mimica

Prompters Dušanka Vukić, Marija Nedeljkov

Assistant Director Aleksandar Marković

Assistant Set Designer Ema Stojković Jerinić

Assistant Costume Designer Margareta Marinković

Assistant Composer Nikola Dragović

Producer in training Igor Milakov

Cast:

Caligula Igor Đorđević

Caesonia Sena Đorović

Helicon Đorđe Marković/Miloš Đorđević

Cherea Bojan Žirović

Scipio Nemanja Stamatović

Mereia Petar Božović

Senectus Dimitrije Ilić

Octavius Vladan Gajović

Lepidus Zoran Ćosić

Mucius Bojan Krivokapić

Wife of Mucius Sanja Marković

Violoncello Player Aleksandra Lazin

Dancers: Olga Olćan, Iva Ignjatović, Čedomir Radonjić

LIght Operater Srđan Mićević

Make-up Marko Dukić

Stage Chief Branko Perišić

Sound Operater Tihomir Savić i Nebojša Kostić

Sets and Costumes were manufactured in the National Theatre workshops