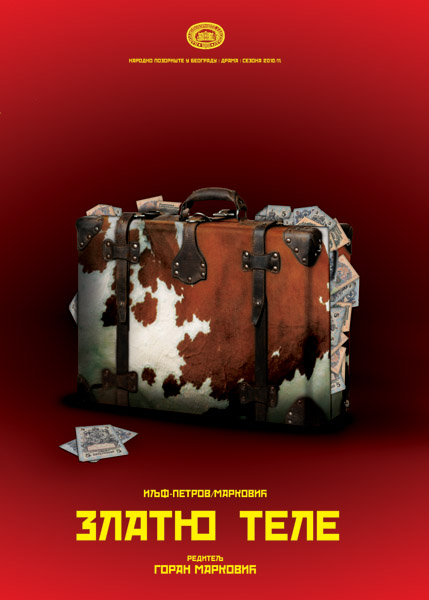

The golden calf

Goran Marković, as per Ilf and Petrov’s novel

INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR

What was the dramatization process like?

I started with the dramatization of The Golden Calf in an airplane, while going to China. Since the flight lasted for sixteen hours, I simply took the time to highlight the text to be taken into account for the drama. The principle is simple: just follow the main plot. I selected only what is important for the main plot, the stealing and cheating. I focused only on Ostap Bender’s project to rob Koreiko, the other swindler. I had to disregard everything else, it doesn’t matter how tempting or funny it was in the novel. I was convinced it was necessary to follow the main plot and it was more important than any other minor plot in the novel. When I observed the plots I chose to ignore, in order to check if I made a mistake and disregarded something worthwhile, I saw that it was not a mistake and that my concept was correct. I read the novel as a young man and now I have read it again, this time from the point of view of a half a century older person. However, during dramatization, in the process of selection of what is important for the play and what isn’t, I tried to act as if I have never read the novel before and only wanted to know what it is about. I tried to behave like someone who shall never find out everything that Ostap Bender undertakes and speaks outside the main plot. I regretted some of the things, but I tried to be stern.As a dramaturge, I was satisfied when I read your dramatization; I regret only that you chose to discard the character of Varvara. The fact is that the characters in dramas are mainly male, two thirds are male and one third are female, so when you get rid of one half out of one third, then… Out of two female characters in the play, only one remained and she has a tiny role. I guess, that’s why I took the Varvara’s story and gave it to Kozlevich, who was somewhat disregarded as a character in the play.You wrote Kozlevich’s part in verse. The cause for this was yet another character, Vasisualy Lohankin. His character was disposed of, as well as many other characters; however, he speaks in verse in the novel, which was very suitable for Kozlevich. Koylevich’s role is minor, but very important for the story. Then I thought of a car spare parts seller from Užice, who spoke in verse all his life. I told you about him and it was a good starting point for you to develop and write Kozlevich’s part.

My intention was to stage the play on the smaller stage in the Theatre, the “Raša Plaović” Stage. The Golden Calf by Ilf and Petrov. I planned this move thinking about Lane (Gutović). Then, while talking to my friend Skerla, I got an inspiration. Then, you said, “Well, this is destiny. I have just read the novel. I would like to direct it.” Then you made such a production that the play had to be moved to the Main Stage.

The most dramatic issue is whether the Ilf and Petrov’s humour and charismatic personality of Ostap Bender shall find their place in this world. Without a doubt, our life today is very similar to the one of more than eighty years ago in the Soviet Union, when The Golden Calf was written. The transition is similar to the period of great social upheaval in the Soviet Union, the so-called NEP (New Economic Plan). Both the then Soviet society and our society today have a similar trait I would like to call – the crimocracy. It’s the time of crime, domination of crime as a basic trait in the society. Today, we live in the society that portrays sights of crime. When in the street, you find yourself surrounded with young man dressed as criminals, while some of young women seem to impersonate prostitutes. This dreadful downfall is similar to what Ilf and Petrov portray in their work. However, they make jokes with it and have so much compassion for their characters, while we find ourselves overwhelmed with what’s happening in our country. The question remains, however, whether the humour shall work and whether it shall find its place here, or not.I have to say – I believe it will. It will from a psychological point of view. You are right when you say that we are overwhelmed with what’s happening, but as a theatre-goer, I need a vent, because I know where I live. The fact that Ostap Bender is appealing, as well as other characters, also the fact that I can identify with them and find a sort of gentle irony in it, is what can enable catharsis and understanding in me. If you portrayed the rule of crime as such, it would be overwhelming and unbearable. However, if there is a crack in there, where I can go through, to be happy and laugh, I will find reality, presented that way, acceptable, even though apocalyptic. Therefore, I believe that the play will be a success and that audience would want to see it.My view is not opposite to yours. I believe that laughter can be a form of screaming; nothing that doesn’t hurt cannot be funny. A man has to have an issue to find something worth laughing at. It’s only a matter of the manner how we express pain, either by crying or laughing.

The way we cry! It’s easier to laugh, one feels superior.

There is an issue of whether the key to comedy will work. In my opinion, the comedy is the only genre that is subversive, as opposed to every other. It has no other meaning except to break up things, to dismantle them. One doesn’t have to have any other motive but to laugh and then one exploits it, prolongs the strain of comic situations. As opposed to, for instance, melodrama that is very good in analysis of family, society… Melodrama is about an emotional relationship obstructed by difficulties. However, the unaccomplished love affair is always essentially connected to social interactions, to the structure of society. Or, for instance, the horror. There is a dark force threatening an individual; it is the definition of the horror… Each of the genres has its commitments and restraints and finds itself fixed within them. Comedy is the only genre that does not have that. Comedy is free. One finds something that causes comic situation and works on that for as long as it takes, without any specific purpose. Of course, I refer to the mechanism of comedy only.

You do not speak about comedy, you refer to comical – the things that cause laughter; nevertheless, there is the function of social criticism. The criticism of faults, in either an individual, or his character, situations or society itself…

It goes without saying. There are many subtypes: satire, comedy of situation, comedy of character, etc. As a director of the play, I wanted to make a connection with the slapstick comedy. The slapstick is a sort of the most elementary and simplest comedy that has its roots in silent movies. This is why I insisted on silent films and introduced extracts in the play. Although there are extracts from very important films of Soviet cinematography, I also introduced some of the marginal films, as well. This was used to make miles of film, slapstick miles, to make the production work in this direction and not any other. The play had a potential to develop as a comedy in different directions. I chose this one. We will see if I have succeeded. This is the reason why I brought in the orchestra, just like in a silent movie, to introduce developments both on the screen and on the stage. It will also serve to downgrade the apparent seriousness of situations in the play. I want to make a statement – This is just fun, everything is just an illusion and has no substance whatsoever.

Why this statement?

As I said, an illusion. I want the audience, when the play finishes, to say to themselves, ‘Ha, this was not that light after all’.That is called litotes in literature, an understatement in which an affirmative is expressed by the negative of the contrary. The way you wanted to express yourself as a director is through litotes… in order to alleviate the burden to the utmost extent. And we are back to the beginning of our interview; so, this was your way to digest the reality we live in.I should say that while doing the dramatization of The Golden Calf, I discovered that characters created by Ilf and Petrov have been revived very often. For instance, the Society in Alan Ford comic strip has been copied from The Golden Calf. Then, there is the famous Italian film Persons Unknown, or our own Balkan Express. Theme of funny, unskilful gang of amiable rascals has been copied many times, without referring to the original. The first I consider legitimate, the latter I don’t. Be it as it may, I like all the mentioned examples, so that’s the reason I took on The Golden Calf. Ostap is a man of style and spirit and therefore his profession can be tolerated. He is a thief, but he knows “approximately 400 relatively legitimate ways of depriving others from their possessions”. The sentence is a core of what makes him a poet of theft. The point of my play is to show that Ostap steals out of love for stealing and not merely for personal gain. Other (our) thieves simply strive to steal, while Ostap Bender transforms the action into a creation that is a goal itself.

Interview by Ivana Dimić

ILF and PETROV

ILF and PETROV

Ilf (Ilya Arnoldovich Faynzilberg, 1897-1937) and Petrov (Yevgeni Petrovich Katayev, 1903-1942) are Russian writers. They did most of their writing together and their most popular novels The Twelve Chairs (1928) and The Little Golden Calf (1931) feature Ostap Bender, a character representing a modern con man whose adventures are portrayed in satirical sketches of reality.

Larousse Encyclopedia (publ. by Vuk Karadzic)

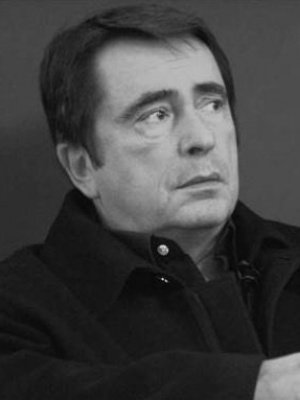

GORAN MARKOVIĆ

GORAN MARKOVIĆ

Goran was born in Belgrade in 1946. He graduated in film directing at the Film Academy FAMU in Prague, Czechoslovakia. Upon graduation, between 1970 and 1976, he made documentaries for television; he produced approximately fifty documentaries. Since 1976, he has been engaged exclusively in writing and directing films. He has produced eleven films and one TV series so far, mostly according to his own scripts. In 1978, he started working at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, as an Assistant Professor and taught actors. Subsequently, he became a standing Professor of Film Directing and he now teaches students attending master studies at the same school. FILMS: Specijalno vaspitanje (The Special Discipline), Nacionalna klasa (The National Class), Variola vera (Variola Vera), Tajvanska canasta (Taiwanese Canasta), Već viđeno (Déjà vu), Sabirni centar (The Meeting Point), Tito i ja (Tito and Me), Urnebesna tragedija (The Tragedy Burlesque), Srbija nulte godine (Serbia, Year Zero), Kordon (The Cordon) and Turneja (The Tour). The films have won numerous awards in festivals of Venice, Berlin, San Sebastian, Valencia, London, Montreal, Montpellier, etc. There have been three retrospectives of Goran Marković’s films organized in France so far, in La Rochelle, Montpellier and Strasbourg. In 1987, at the retrospective of Yugoslav films in Pompidou Centre, Paris, Goran Marković has been presented with three films. In 2002, the Rotterdam International Film Festival, Kinoteka in Ljubljana and Kinoteka in Zagreb have organized a comprehensive retrospective of the author’s films. THEATRE PRODUCTIONS: Goran Marković’s theatre opus consists of the following dramas: Turneja (The Tour), Govorna mana (The Speech Defect), Osma sednica ili Zivot je san (The Eighth Convention or Life Is a Dream), Pandorina kutija (Pandora’s Box), Parovi (The Couples), Vila Sasino (Villa Sashino), Delirium tremens (Delirium Tremens) and Falsifikator (The Falsifier). He won Sterija’s Award for The Tour in 1997. At the competition organized by Goethe-Institut, on occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, his play The Falsifier made it into the six best plays in Europe and was performed at the review in Dresden, in 2009. Goran directed several productions: Pazarni dan (A Market Day) by A. Popović, Beogradska trilogija (The Belgrade Trilogy) by B. Srbljanović, Pomorandžina kora (The Orange Peel) by M. Pelević (he received the best director award at the Yugoslav Theatres’ Festival in Užice this year), Terapija (The Therapy) by J. Cvetanović; as well as his own plays: Pandora’s Box, Delirium Tremens, The Eighth Convention or Life Is a Dream, The Falsifier and The Golden Calf – his own dramatization of the novel by the same name, written by Ilf and Petrov. BOOKS: He wrote the book named The Czech School Does Not Exist, a short novel Tito and Me and A Year, novel in the form of a diary. Goran published a collection of his plays The Eighth Convention and Other Dramas and a novel Little Secrets.

Premiere performance

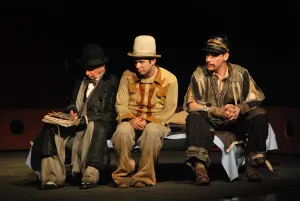

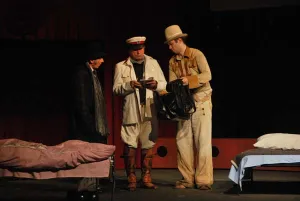

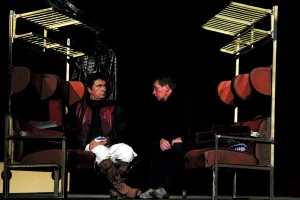

Premiere, Оctober 6, 2010 / Main stage

Translation from Russian by Nikola Nikolić

Dramatization and direction Goran Marković

Dramaturge Ivana Dimić

Set Designer Boris Maksimović

Costume Designer Ljiljana Petrović

Music Composer Zoran Simjanović

Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Video presentations author Andreja Maričić

Stage fights dr Aleksandar Tasković

Premiere cast:

Ostap Bender Milan Gutović

Koreiko Igor Đorđević

Panikovski Vlastimir-Đuza Stojiljković

Shura Balaganov Hadži Nenad Maričić

Adam Kozljevich Darko Tomović

President of the Executive Committee and the Traveller Radovan Miljanić

Zosya Sinjicka Ivana Jovanović

Funt [Rade Marković] / Radovan Miljanić

The Young Man Ivan Zarić

Orchestra:Zeina Živković (piano and percussions), Ljiljana Cincar Danilović (accordion), Kosta Naumović (violin), Zoran Kočišević (contrabass)

Extras: Milan Šavija, Aleksandar Vukić, Ognjen Vitković, Sergije Andrijević, Zoran Trifunović

Assistant Director Andreja Maričić

Assistant Costume Designer Tina Bukumirović

Assistant Set Designer Maja Nanović

Music recorded by Zoran Uzelac

Producer of Production Jasmina Urošević

Stage Manager Miloš Obrenović

Prompter Danica Stevanović

House Carpenter Zoran Mirić

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

Lighting Srđan Mićević

Sound Operator Nebojša Kostić

Costumes and set were manufactured in workshops of the National Theatre in Belgrade.

The production features excerpts from the following films: “The Girl with a Hat Box” by Boris Barnet; “The Sixth Part of the World” and “The Man with a Movie Camera” by Dziga Vertov; “October”, “The Battleship Potemkin"and “Strike" by Sergei Eisenstein; “Aelita" by Yakov Protazanov; “Kosty the Shepherd" by Grigori Aleksandrovich.