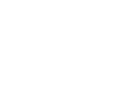

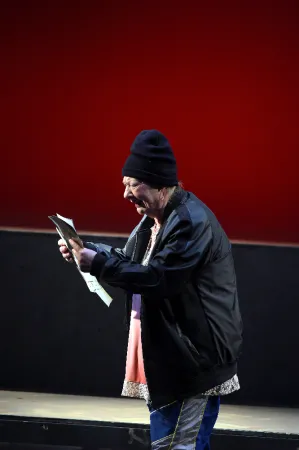

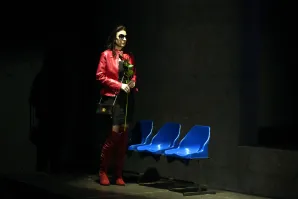

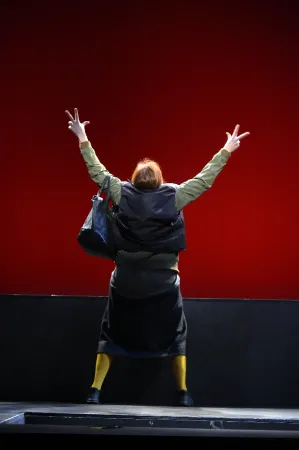

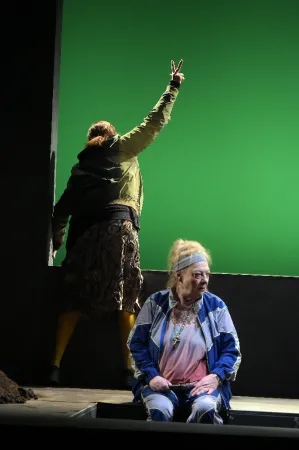

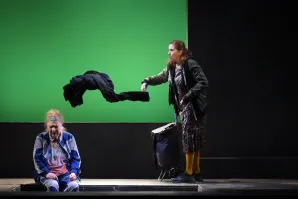

The nineties

drama by Goran Milenković

.jpg)

A WORD FROM A DRAMATURGE

In an interview Egon Savin spontaneously lists basic terminology that may have found its way in an imaginary vocabulary of the 1990s, “turbo-folk, drugs, shootouts, hamburgers, ethnical cleansing, Slobodan, trading booths, smuggling, refrigerator trucks, flee markets on pavement, foreign currency, leather jackets, rapping, JUL, military uniforms, crimes, TV News, Dafina, Zemun Clan… But also – rallies, demonstrations, clashes with the police, students, drums, whistles, police barricades (…) aerial bombing, sirens, shelters, locators, targets pinned to one’s back… “ Upon listing these terms, the stage director states, “the 1990s in Serbia were an extremely theatrical sociopsychological phenomenon.” This statement is priceless, because it introduces the issue of what art stands to benefit from this “real life” theatricality and what has been created in the sphere of art in this sense. We cannot say that there have not been any works of art that dealt directly with the theme of this, historically speaking, very important decade. In our films, theatre productions and prose works, as well as in numerous documentary interpretations of the 1990s events, we can see all of the abovementioned, including petrol canisters in streets, rave parties, omnipresent guns, prostitution, etc. However, we still have a feeling that the real expression of what we lived through in the 1990s is lacking. In the domain of art, we keep on feeling that something is missing from the presentation of the period, despite of all the efforts to portray the full spectrum of events we know from the period, as if the reality is in abundance, while there is too little of art in there. It may be the case that we have disregarded the aesthetic standard that “difference between art and the event is always absolute”, as T. S. Eliot said. By listing examples from the tradition of artistic presentation of historical events, Eliot warns that“Impressions and experiences which are important for the man may take no place in the poetry, and those which become important in the poetry may play quite a negligible part in the man.” These observations about differences between artistic truth and individual, floating and undefined emotions characteristic of experience of reality have been expressed in professor Boško Milin’s praise to Goran Milenković, “The play is as dark as the world in which we live in, but the world is not the work of art and your play is.” Goran Milenković’s success could very well be in the fact that he resisted this challenge of “caricaturing and exaggeration”, and for avoiding immediate reaction to events that seemed perfect for urgent artistic modelling (a film about bombing was made while the actual bombing was still going on). It may be that writing after a time distance, the conscious distance from detailed reproduction of real and well-known events, is the reason why we got an extraordinary play to this threadbare theme at last. Instead of attempting to encompass all events from the 1990s (which would require a novel-like and intricate structure), Milenković decides on portraying only several typical situations and characters. We observe five women, two mothers of assassinated criminals, a wife and a daughter of a perpetually absent husband and father, and a mistress of an assassinated judge/ politician/member of a crime clan; and everything is presented in three situations, given in only six scenes. Here, we can almost speak of a “lack of subject matter”, as Mirjana Miočinović noticed while writing about Aleksandar Popović, as if the play came to existence ‘from nowhere’.” In Milenković’s play, the same as in Popović’s, everything is focused on stage limited events, all determining events take place (or have already happened) outside the stage. On stage, we can see only the events’ echoes in the characters’ souls. Nonetheless, it is more than enough, because the playwright succeeds in building a comprehensive plot only through the means of dialogue, without digressions and descriptions, “thus, without all the things the authentic theatre space does not tolerate” (Miočinović). At the same time, despite the lack of description The 1990s possess documentary value, but also, according to the stage director Savin, “on the other hand, by distancing from documentary it possesses unique aesthetics” (…) In every segment of the play the “black humour and sarcasm, and Milenković’s ability to present tragedy” (Savin) come to the first plan. And already with these several traits of Goran Milenković’s writing, we can see that he relies on tradition of modern tragicomedy, which had its representatives in Serbian drama, starting from Popović and Simović, and all the way back to Nušić and Sterija. This new, authentic and, shall we say, poetic voice was missing from our contemporary drama.

Slavko Milanović

GORAN MILENKOVIĆ

GORAN MILENKOVIĆ

Goran Milenković (1983, Pirot) graduated at the Department of Dramaturgy. He wrote plays Let Us Rest in Peace that won the “Slobodan Selenić” Award (2016) and Across the River, which won the Radio-Drama of the Year Award at Radio Belgrade (2017). He has written screenplays for several episodes of the cult TV series Open Door (2015). As an almost unknown writer, of not so young a generation, he is the first Serbian writer who is having three premieres in the capital city in the period of three weeks (2018). His

Belgrade trilogy starts with The 1990s, directed by Egon Savin, in the National Theatre, after 6 years of joint attempts to stage it in one of theatres: followed by The Adulteresses, directed by Maja Maletković, which will be performed in a boxing ring, and finally, the premiere of Borderline Beauty, directed by Stevan Bodroža, which will premiere in a techno nightclub in Belgrade. He keeps on writing.

EGON SAVIN

EGON SAVIN

Egon Savin is a Professor of Stage Directing at the Faculty of Drama Arts in Belgrade. He staged numerous productions in all the most significant theatres in former Yugoslavia and his productions toured Nancy, Paris, Warsaw, Tel Aviv, Vienna, New York, Chicago. He has been presented with numerous stage directing awards. Savin has had much success in all production models staged in the country, starting from productions that rounded up a group of young actors (co-conspirators) in 1970s, to productions in theatres of national importance such as the National Theatre in Belgrade, Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad, Montenegrin National Theatre in Podgorica, Macedonian National Theatre, Slovene National Theatre, Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Atelier 212 Theatre, Belgrade Drama Theatre, etc. He stages plays by national and international classics with a lot of success; in his productions, he uncovers tangible clues, thus revealing the essential power of theatre in our time and connecting the plays and their authors to our territory and time. Egon Savin has directed the following plays in the National Theatre: a comedy Cyrano de Bergerac by Rostand (premiere, 22 March 1991); Kir Janja (premiere, 25 December 1992) and The Upstart by Sterija (premiere, 18 January 1998); drama Demon by Isaac Bashevis Singer (premiere 15 March 2000); States of Shock by Sam Shepard (premiere, 26 October 2001) and Death and the Dervish after the novel by Meša Selimović (premiere, 27 December 2008), The Deceased by Nušić (premiere, 26 December 2009), The Misanthrope by Molière (premiere 19 May 2012), The Miracle in Shargan by Ljubomir Simović (premiere, 20 February 2015). Kir Janja is the longest running production of the National Theatre – it has been performed for 26 years.

Premiere performance

Premiere, 27th March 2018. / „Raša Plaović” Stage

Stage Directing and Adaptation Egon Savin

Set Designer Vesna Popović

Costume Designer Stefan Savković

Music Composer Borа Đorđević and ”FISH SOUP”

Dramaturge Slavko Milanović

Stage Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Artistic Associate Petar Antonović

Executive Producer Milorad Jovanović

Producer Jasmina Urošević

Stage Manager Sandra Rokvić

Prompters Gordana Perovski, Anja Gavrilović

Premiere Cast:

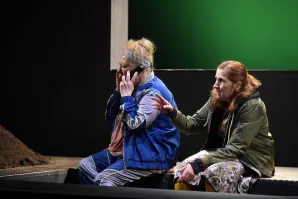

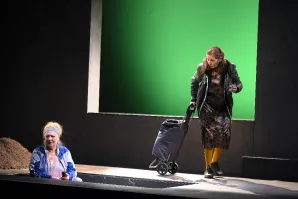

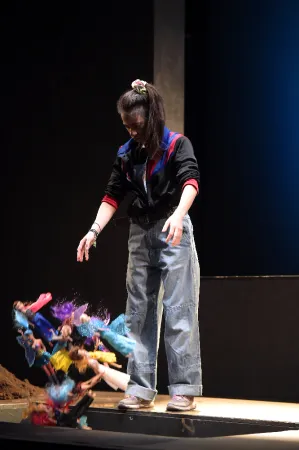

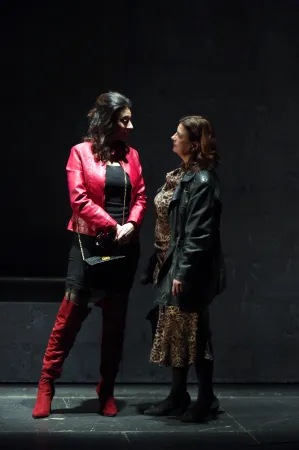

Zora Radmila Živković

Ranka Olga Odanović

Lena Anastasia Mandić

Ceca Milica Gojković

Sonja Dragana Varagić

Lighting Master Srđan Mićević

Make Up Marko Dukić

Stage Master Zoran Mirić

Sound Master Nebojša Kostić

Assistant producer Aleksandra Jovanović (student)

Costumes and set were made in the National Theatre’s workshops.