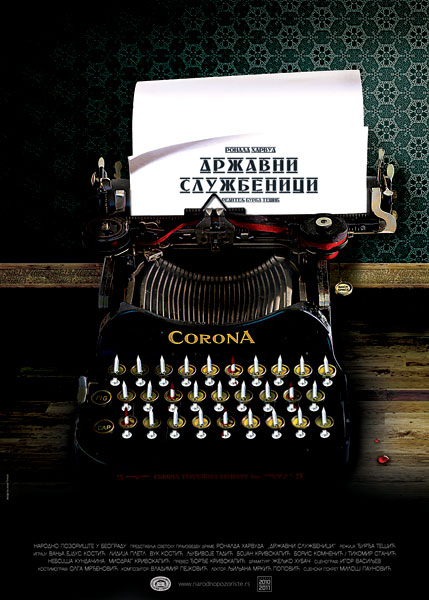

Civil servants

drama by Ronald Harwood

А LIE AS TRUTH

WORD FROM A DRAMATURGE

Harwood’s play Public Servants introduces several questions regarding morality at times in which morality is a burden, especially inside the structure we call state apparatus; many would say that the way the play initiates these issues is utopian and don-quixotic. Ralph Wigram, an official in Great Britain’s Foreign Office, gets into possession of secret intelligence about the strength of Nazi Germany’s air force that surpasses the British air force by far and decides to warn the nation about danger that has been hidden by the Government who persuades its citizens into supremacy of British war machinery at the time (autumn 1936). So, Harwood processes this seemingly simplified dramatic situation and it grows into a personal tragedy of, from a dramatic point of view, a low-mimetic character and into a universal and timeless story.

• How many times have you heard a lie from the state apparatus stated publicly, owing to the mass of indifferent clerks who never change, ever since Gogol’s time, that has been presented as truth, an ideology that inevitably leads into tragedy, on whose remains a new lie is born to protect the interests of the state oligarchy, the same bureaucratic dragon that rules on behalf of people, by protecting only its own interests?

• How many times have you said nothing to such a lie?

• How many times have you rephrased the lie in front of other people, presenting it as the truth?

• Where and when have you started searching for reasons to defend the false truth in a discussion in which you felt morally inferior?

• When have you stopped feeling morally inferior?

• When did you believe in a lie?

• Is your feeling of superiority based on common sense?

• What happens to your reason?

Theatre, possibly, does not have the power to change the world; however, we, the theatre artists, believe that theatre is a significant catalyst of necessary processes of change when man’s beliefs and returning to oneself are concerned. If the questions above start concerning you after you have seen the Public Servants we shall be a one human soul happier society. This is what we believe in…

Željko Hubač

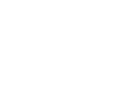

RONALD HARWOOD – Instead of a Biography

RONALD HARWOOD – Instead of a Biography

DRAMA PLAYWRIGHT AS A MORALIST

And situations and not to other ones. The answer, I suppose, is the same one I give when someone asks me how long it takes to write a drama. “Sixty-two years”, I say, which can sound laconic, however, it is true. And so,(…) I need to say something about my past. The War and facts about the Holocaust in 1945 were, and still are, dominant events in my life. We, the Jewish kids, were taken to a cinema where we saw films from Belsen, Dachau and Auschwitz. Those nightmares never left me. (…)

Writing came accidentally. Or, at least, it seems that way. On 21st March 1969, South African police opened fire on protestors in Sharpeville in Transvaal, and killed 56 Africans; most of them were shot in the back. It was, trust me, the shocking event that changed my future. My father in law gave me a typing machine for my 25th birthday; I was jobless and on the dole at the time; my wife was pregnant with our first child. More importantly, I was upset with the massacre in Transvaal, so I wrote my first novel in three weeks. When I finished the novel, I was overwhelmed with such excitement, the kind I never felt before, that I literally could not catch my breath. The book was published in 1960, the reviews were good and I thought that I would soon get the Nobel Prize in Literature. (…)

Although, I admit to believe in pressure from the world onto tyrannical regimes, I was interested into making my behaviour, my voice, tightly connected to my private need to be accepted as a decent, upright man. (…) In 1968, I wrote the screenplay for one of the masterpieces of the twentieth century, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, for a film in which Tom Courtenay played the leading role. The novel describes a good day in the hero’s life in the gulag. It is not only about physical survival, it is about preserving moral integrity in the harshest of conditions. Therefore, the question “How would I have behaved in such circumstances?” is what I have frequently asked myself. (…)

Twelve years ago, I joined the English PEN society, the founding centre of International PEN Club, the only international association of writers in the world. In the beginning, I was a member of the Executive Committee, then I was the President of Writers in Prison Committee, and afterwards I succeeded Antonia Frazer as a President of English PEN Club. Three years ago, in Santiago de Compostela, I was elected a President of International PEN Club. (…) On the job, I met men and women who fought tyranny and injustice. List of governments that suppress freedom is depressingly long. I had the honour to meet men and women who spent years in jail, who were tortured, whose families were threatened to and who endured injustice, but they continued with their protest. When I meet each one of them, the question starts shouting in my head, “Would I have behaved the same? Would I have been so brave?”

(…) I wanted to find out more about the Berlin Group (a group that had a task to make an indictment for war crimes against Wilhelm Furtwangler, the Director of Berlin Philharmonics, who stayed in Germany after Nazis came into power – edit.). I called a lady researcher who used to help me before and asked her to find out everything she can about the American group in Berlin. She conducted research in Bohn, Berlin, Arlington (USA) and came up with nothing. Yes, there was a group, but there simply was no information about its work. The moment I heard this, the drama was born in my head (drama about Furtwangler, Taking Sides – edit.). When the drama was produced, I have received numerous letters. Some letters were from the American investigators, like Major Arnold, who said that my Major was not brutal enough; other letters with personal accounts of Furtwangler’s kindness, arrogance, anti-Semitism; in other words, everything corroborated the moral unclearness that was in the heart of the drama. (…) It is sad, but unfortunately, it is true that only a few individuals act out of moral imperative. (…)

The British were leaders in pursuing Nazi war criminals in Nurnberg; Winston Churchill recommended, at one point, to shoot them without trial. At the end of 1946, the mood changed. (…) Forty-five years later, it changed again. Because of the lists that Simon Wiesenthal Centre and the Embassy of ex Soviet Union submitted, and because of investigations on similar crimes led by police of Australia and Canada, the names of alleged war criminals who were alive and living in Britain, were submitted to British Government. The Government stalled for a while, as governments usually do, and then decided to change the law. (…) War Crimes Unit was established in Scotland Yard and investigations started to track down a dozen of people who were still alive and against whom there were evidence – both reliable and unreliable. (…) One person was arrested and indicted, an eighty-year-old Latvian, who worked on construction and lived in the south of England; he led a life worth of respect and fully obeyed the law of the country. The British press and TV gave extensive reports on the arrest. (…)

This brings me back to my drama The Handyman. Two close friends came to see the play about Furtwangler, Taking Sides, and after the show one of them said, “Do you know what you should write next? You should write about the old man who was indicted of war crimes.” As soon as I heard this, I knew, just as I knew in Furtwangler’s case, that there is a drama in there that should be written. (…) Should a civilized society prosecute and imprison old men for crimes they allegedly committed fifty years ago? Can there be reliable evidence that can sustain in court? Does the accused have the same sources as the ones who charge him to create an alibi (very often the only defence in murder trials)? Can he find witnesses to testify that he has not been in a certain place at a certain time? (…)

Drama does not provide any conclusions (…) I leave it to audience to decide for themselves. As a result, the method provokes discussion. This does not mean that I have no opinion about what is right and what is wrong in the circumstances, but I believe that playwrights should ask questions and not give answers. It is my opinion, an opinion of the playwright who had the courage to deal with these moral dilemmas. I despise didactic dramas of the sixties and seventies. I loathe playwrights who serve conclusions. I am not a fan of George Bernard Shaw. Traditional and historic role of a playwright, which dates back to the first playwrights in ancient Greece, was to ask questions, investigate “what is a man’s place in general scheme of things”, and to question, scrutinize and present moral categories.

Taken from Ronald Harwood’s lecture

British Council in Belgrade, 3rd December 1996, Published in “Reč” Magazine, no. 34, June 1997

DJURDJA TESIC

DJURDJA TESIC

She was born on 4 May 1977, in Belgrade. She graduated Theatre directing from the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade in 2002. She directed the following performances:

The Black by Damir Vijuk (Bitef Theatre, 2000)

Casanova by David Greig (Serbian National Theatre, Novi Sad, 2002)

The Black Milk by Vasily Sigarev (The National Theatre in Belgrade, 2003)

Everyman by Goran Stefanovski (Atelier 212, Belgrade)

Blasted by Sarah Kane (The Belgrade Drama Theatre, 2005)

Momo by Mihail Ende (Duško Radović theatre, Belgrade)

Waiting for Godo by S.Beckett (Atelier 212, Belgrade)

Miss Julia by A.Strindberg (The National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka, 2007)

The Three Sisters by A.P.Chekhov (The National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka, 2007)

Milk by V.Kacikonuris (The Belgrade Drama Theatre, Belgrade, 2008)

Pool (No Water) by M. Ravenhill (National Theatre in Belgrade, 2009)

Lord of the Flies by W. Golding (Boško Buha Theatre, 2009)

The Wedding by J. S. Popović (National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka, 2010)

Novecento – Boka Hotel

(Cultural Centre Tivat, 2010)

Premiere performance

Premiere 4th November 2010 / "Raša Plaović" Stage

Translated by Đorđe Krivokapić

Director Đurđa Tešić

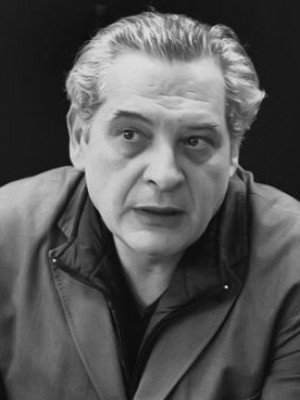

Dramaturge Željko Hubač

Set Designer Igor Vasiljev

Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Composer Vladimir Pejković

Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Stage Movement Miloš Paunović

Premiere Cast:

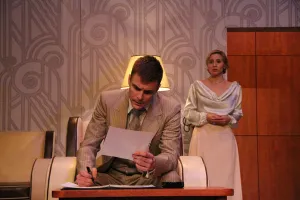

Ava Wigram Vanja Ejdus Kostić

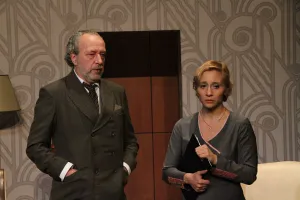

Dr Pamela Lawford Lidija Pletl

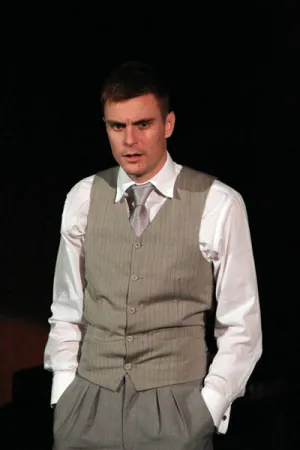

Ralph Wigram Vuk Kostić

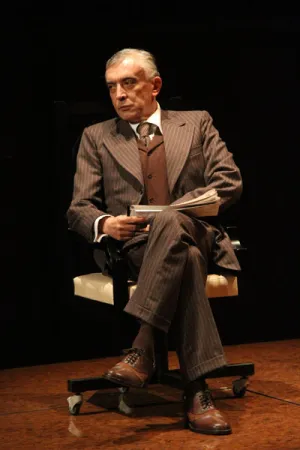

Sir Robert Vansittart Ljubivoje Tadić

Nigel Cooper Bojan Krivokapić

Desmond Morton Boris Komnenić / Tihomir Stanić

Sir Maurice Hankey Nebojša Kundačina

Sir Walter Runciman Miodrag Krivokapić

Producer Nemanja Konstantinović

Stage Manager Saša Tanasković

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Student volonter Branka Bešević Gajić

Assistant Costume Designer Marija Tavčar

Lighting Operater Srđan Mićević

Make-Up Dragoljub Jeremić

Stage Master Nevenko Radanović

Sound Operater Dejan Dražić

Male costumes molder Drena Drinić

Female costumes molder Radmila Marković

Shoe molder Milan Rakić

Set and costumes were manufactured in the workshops

of the National Theatre in Belgrade.