The deceased

comedy by Branislav Nušić

THERE IS NO DRAMA WITHOUT COMEDY OR COMEDY WITHOUT DRAMA

In preface for the book of selected plays from period between the two world wars, Mirjana Miočinović states, “Serbian drama between the wars, if we leave Nušić out, does not have a single star”. All drama and theatre historians would agree with her today. However, it was different in Nušić’s time. Almost all literary and theatre critics used to find at least one fault with Nušić at that time. They disapproved with his “superficiality” and “ease”, “cheap effects”, “primitive humour”, “sharp account of exchanges from the open market”, “banal commonplace”, “vulgarity”, “unskilled copycatting of Gogol”, “caricaturing”, for “easy laughter, for the sake of laughter itself”, “presentation of lack of taste and folly”, “routine”, “inclination to jokes” and so on. Some of Nušić’s critics showed even more thoroughness when repudiation of his work was concerned, stressing that they are doing this “from the position of pure art”. One of them (Ž. Milićević in The Politika) grieves that the Novi Sad Theatre manager did not “refuse Nušić’s failure of a play“(Sumnjivo lice/The Suspicious Character), while the other (signed as R in The Vijenac) laments that the play “should stay in drawer for all eternity (…) and never see the light of day and stage”. Aware of the fact that after opening night and triumph with audience, as a rule, there was an underestimating and frequently unscrupulous review to follow, Nušić ridiculed his critics in a funny way, often at his own expense. Therefore, in the preface of Sumnjivo lice he “confesses” that the play has been written under direct influence of Auditor by Gogol in order “to prevent the critics’ boasting for having exposed this”. With the aim to ward off the opportunity for academic lectures on rules of classic comedy, he subtitled his plays as “a joke” (Običan čovek/Ordinary Man, Gospođa ministarka/Mrs. Cabinet Minister’s Wife), “joyful play” (Beograd nekad i sad/Belgrade, Past and Present) and in one case simply – “a piece” (World). Influential critics adjoined to The Serbian Literary Herald thought of him as of a “vaudevillist”. Even when they could not attribute “superficiality” and “laughter, for the sake of laughter”, those “literary judges”, as Nušić calls them in the letter to his daughter Gita Predić, find that his comedy “a comedy of temperament, which in its value falls behind the comedy of character, nurtured only by Sterija Popović”. Overwhelmed with animosity for the only fruitful and successful playwright (Slobodan Jovanović: “Our drama currently can boast by Nušić only. Luckily, he is productive as three playwrights put together.”), the literary judges fail to realize that Nušić’s predecessors (Joakim Vujić, Jovan Sterija Popović, Kosta Trifković, Milovan Glišić) have been characterized as “despised `types` of comedy makers and jesters”, who had to pay for “sweet taste of their success” with “bitterness of underestimation” (Josip Lešić). Nušić’s drama opus has been even less appreciated. Only the rare critics have given him due attention like Slobodan Jovanović (“Nušić has tried his hand in almost all theatre categories and we could say, without any exaggeration, that he alone is worth a group of playwrights”). This solitary voice of recognition came too late and did not mean much in the sea of negative reviews for Nušić’s social and historic plays that are as numerous as his comedies. Egon Savin finds that if these plays had received the response they deserve, Nušić would have continued writing the social drama he loved and admired, starting from Sophocles to Strindberg. Therefore, “instead of plays which have not been written, there are his comedies whose popularity shall not be excelled in the Serbian theatre”. Only at the end of his life, almost on a deathbed, Nušić got satisfaction and acknowledgement for The Deceased – “almost unanimous positive reviews” (as per Raško V. Jovanović). Nevertheless, if we take a closer look at the “almost unanimous positive reviews”, we can see that there were still reservations: the critics praise Nušić “the times have made him forget about entertaining the crowd” and for (as if there is no playwright’s merit!) being forced to “worry, get angry, and to use the sharp whip of satire instead of the soft rubber stick of joke” (M. Savković). Cultural climate at the time when Nušić wrote is well represented with the fact that “not a single study has been written (except later, in 1930s, at the end of the writer’s life)” about comedies of the most popular and staged playwright (J. Lešić). According to Egon Savin, who confirms this statement with his directing, Nušić is an “author with a streak of genius” – “The theatre Nušić wrote for was far behind European cultural affairs. Nušić was ahead of Serbian theatre for a half of century”. However, Nušić was given both literal and review rehabilitation shortly after his death. Not long after the II World War, there was, one can say, a delighted come back of Nušić, brought about by a generation of educated directors and actors. This generation was skilled in all elements of scenic expression, it was liberated from obsolete theoretical classifications, especially concerning the drama genre; for this generation Nušić represented a definite significance and his works were a fruitful soil for scenic research. The old allegations, that Nušić’s plays are burdened with comical and comedies (The Deceased) with drama elements, became irrelevant with the first competent staging. When speaking about these allegations, Egon Savin reminds about theatre experience and specific scenic act “Modern theatre has proved that every comedy possesses a little of drama and every drama a little of comedy in itself. Comical and dramatic are in constant touch.” He asks “May we differentiate the theatre talents to drama and comedy?” There has been a series of Nušić’s plays performed in 1950s and 1960s, starting with famous directing of Sumnjivo lice by Soja Jovanović (Academic Theatre, 1948), proving that there is an endless scenic potential of Nušić’s plays. Every significant director in former Yugoslavia worked on Nušić’s plays at the time of avant-garde in the sixties and domination of “directors’ theatre”, even when radical performances are concerned. In that view, every theatrologist, as well as drama and theatre theoretic, studied Nušić, who is now considered a classic. Starting ground for Egon Savin is that “there is a great challenge for modern directing to show that Nušić - the drama writer and Nušić - the comedy writer are one person – one theatrical entity.” It represents the basis for researches conducted during rehearsals of The Deceased, as one of the most significant products of our drama literature, suspected for its genre for a long time, both in theory and reviews.

Slavko Milanović

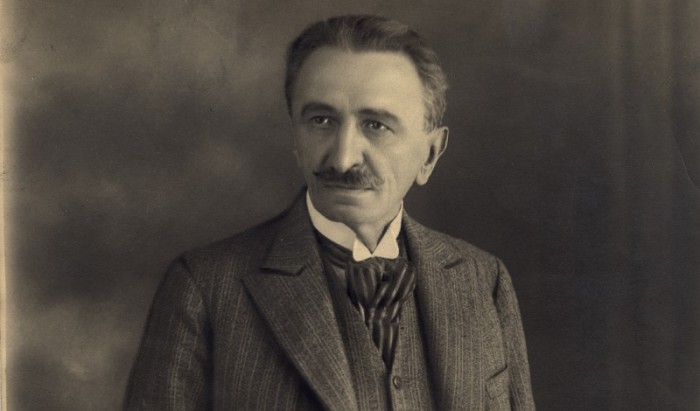

BRANISLAV NUŠIĆ

BRANISLAV NUŠIĆ

1864 He was born as a fourth child to a well-off family of merchant Djordje Nuša and his wife Ljubica on 8th October in Belgrade. They named him Alkibijad. At the time, they lived in Kralja Petra Street in the house situated exactly where the National Bank of Serbia now stands.

1870 The father is forced to move the family to Smederevo after going bankrupt.

1870–74 He attends elementary school in Smederevo, while his father is keeping a shop.

1874–82 He attends Gymnasium (a grammar school; in 1875 he is forced to repeat the first grade) then he becomes an apprentice for a short time in Pančevo and in 1876 he continues his education in a Gymnasium in Belgrade. Together with his cousin Jevta Ugričić he becomes “infected” with theatre.

1882 He graduates and starts using the name - Branislav.

1883 He becomes acquainted with Vojislav Ilić. The acquaintance is his ticket to the best known centre of literary life in Belgrade at that time – the home of Ilić family, where he shall read his first play Narodni poslanik (A Member of a Parliament).

1884 He studies law in Graz, Austria.

1885. He comes back to Belgrade and continues his studies. Nušić volunteers and fights on Serbian side in a war between Serbia and Bulgaria.

1886 He graduates from law school and writes Pripovetke jednog kaplara (Stories of a Corporal).

1887 He publishes a controversial poem Dva Raba (Two Funerals) and criticizes the rule of King Milan and gets sentenced to two years of imprisonment.

1888 He spends a year in a prison in Požarevac and manages to write Protekcija (Protection).

1889 He becomes a civil servant. The Minister of Foreign Affairs appoints him to consulates in Bitola, Priština, Skopje and Serez. Nušić spends the next ten years in diplomatic service.

1891 Nušić and Dragutin Ilić restart and edit Preodnica (An Advance Party).

1893 Nušić marries Darinka Đorđević, a merchant’s daughter, whom he met as a niece of the Consul Bodi in Bitola. The same year, Nušić is appointed a consul in Priština, where Vojislav Ilić works as his clerk.

1899 He is a member of editorial staff in Zvezda, a magazine run by Janko Veselinović.

1900 Nušić is appointed a Secretary in the Ministry of Education and shortly afterward, he becomes a dramaturge and acting manager of the National Theatre in Belgrade.

1901 He edits Pozorišni list (Theatre News).

1902 Nušić retires as per his own demand, because of his dissatisfaction with not being appointed the manager of National Theatre. He gets reinstated and appointed the commissioner for postal and telephone company, which he refuses and gets re-retired. He takes an active part in establishing the Serbian Writers and Artists Association.

1903 He is appointed the Head of National Propaganda Department with the Government as an authority on situation in Serbian territories still under Turks. After the coup of 29th May, he gets retired yet again.

1904–1905 Nušić is a Manager of Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad.

1906–1907 He is an assistant dramaturge in the National Theatre in Belgrade.

1905 Nušić and Mihajlo Sretenović establish Malo decje pozoriste (A Small Children’s Theater) in Belgrade (a predecessor of Roda Theatre founded in 1937).

1907 He elaborates a study on foundation of Montenegrin National Theatre in Cetinje for King Nikola.

1905–1910 He publishes his famous “conversations” in the Politika Newspaper and signs them as Ben Akiba.

1910 Nušić is sentenced to three months of imprisonment for his article Narod i dinastija (The People and the Dynasty) commenting on the relationship between King Petar and Prince Đorđe. He does not serve this sentence on account of the upcoming war. He was given a medal of Sveti Sava and White Eagle.

1908–1912 Nušić is involved in journalism. He is an assistant and editor of the following magazines: Samouprava (Self-Management), Tribuna, Belgrade Newspapers, Daily Newspapers, Guard; as well as with humoristic newspapers such as: Brka (Moustaches), Ćosa (Bald), Satire, Telephone, etc.

1912 He is appointed the first Head of liberated Bitola (during the Balkan war).

1913 Nušić establishes a theatre in liberated Skopje and becomes its manager.

1915 Skopje. His daughter Margita Gita gets married to a writer Milivoj Predic; and the son Strahinja Ban dies while fighting with Bačka company. Nušić retreats with the Serbian army through Albania to Corfu.

1916–1917 He lived in Italy, France and Switzerland. He elaborates The Plan to Rebuild and Rejuvenate National Culture after the War and sends it to the Minister of Education to Corfu in 1917.

1918 He goes back to his duty in Skopje.

1919 Nušić becomes the first Head of Art Department (later the Ministry of Culture) in the Ministry of Education in Belgrade 1922 He got denounced by the church, because of his play Nahod.

1923 He is dismissed from position of the Head of Art Department. He received a medal of Sveti Sava I Class.

1924 A grand celebration of his sixtieth birthday and forty years’ writing anniversary.

1925–1928 Nušić becomes a head of Sarajevo Theatre; he writes Ramadan Nights and uses the pseudonym Halil Delibašić.

1929 Nušić is a librarian of the National Assembly. He finally retires. He receives a medal of the Officer of the Legion of Honour.

1930 He acts in a film Paramunt Review in Vienna. He teaches Rhetoric at the Military Academy and writes a book on the subject. The book is still in use.

1931 Nušić signs a contract with a well-known Belgrade publisher, Geza Kohn, regarding the printing of all his works.

1933 He becomes a member of Serbian Royal Academy. 1934 Upon his first major health crisis, he moves with his family to Hvar Island to recuperate.

1935 Upon the premiere of Bereaved Family in Sofia, he gets a Bulgarian medal of Citizen’s Accomplishment.

1936 After many relocations, he purchased a piece of land and built a house in 1 Rosalia Morton str. (now - Shakespeare str.) and moved in on 15th September.

1937 Nušić gets an operation in Vračar Sanatorium in Belgrade. At the founding assembly of Association of Artists, Scientists and Writers, held on 5th December, he gives a speech and appeals to solidarity against fascism – the famous Cultural Testimony.

1938 Branislav Nušić died in Belgrade, on 19th January. He was buried in his family crypt in Novo groblje (New Graveyard) in Belgrade.

EGON SAVIN director

EGON SAVIN director

Egon Savin currently works as Professor of Directing at the Faculty of Drama Arts in Belgrade and at the Faculty of Drama Arts in Cetinje. He directed more than 80 plays so far. He directed guest performances in Nancy, Paris, Warsaw, Tel Aviv, Vienna, New York, etc. He has received a number of awards. Egon Savin has successfully worked in all production models in the country, starting from non-institutional theatres and off-scenes, to almost all established theatres in ex-Yugoslavia. He successfully directs plays by domestic and international classics and finds tangible clues that discover the essential power of theatre in our time and connect the plays and their authors to a specific space and time. Egon Savin has directed the following plays in the National Theatre: a comedy Cyrano de Bergerac by Rostand (premiere, 22 March 1991); Kir Janja (premiere, 25 December 1992) and Pokondirena tikva by Sterija (premiere, 18 January 1998); drama Demon by Isaac Bashevis Singer (it was played by the name of Teibele and Her Demon; premiere 15 March 2000); States of Shock by Sam Shepard (premiere, 26 October 2001) and The Dervish and Death by Meša Selimović (dramatized by Borislav Mihajlović Mihiz, adapted by Egon Savin; premiere, 27 December 2008).

NUSIC ABOUT THE DECEASED

The interview took place in autumn 1937, several days before the opening night of The Deceased in the National Theatre. Nušić was interviewed by Milan Đoković for the newspaper Pravda. At the time Nušić was staying in “Vračar“ Sanatorium because of his heart condition. The interview reveals that writing of the comedy took some time and that there were at least two versions of the manuscript: The Deceased is my intimate companion from the period of my last winter’s health crisis. I died and came back to life several times at the time. During the ordeal, first edit of The Deceased was lying on my table.

Is it really your custom to take the time for several versions?

No, it isn’t. Nevertheless, this time it was. The Deceased you are going to see on Thursday has almost nothing to do with The Deceased lying on my table while I was ill. If you are interested, I’ll tell you how it happened… I did foresee a play just like the one audience is going to see and I wrote the first act. As a convalescent, probably overwhelmed with the seriousness of my situation and lacking joyfulness as a precondition for writing a comedy, I went with the flow of sentimentality and wrote a completely different play, a psychological drama instead of comedy. It took quite some time to see that it was not what I wanted and to go back to the present version. Moreover, there is still another play by the name of The Deceased in my drawer. I took only the opening act and slightly modified it. Maybe, a skilled observer could notice that the opening is different in tone from other acts in the play… As you can imagine, if I had died last winter, there would have been two deceased in my house. This way, both of us came back to life, The Deceased and I.

Is The Deceased in the same style as your recent comedies?

It is somewhat different in a roughly stressed tendency, certain sharper contrasts in portraying our social circumstances.

Should we, then, expect less or more success?

We shall see. Still, I do not expect The Deceased to reach the success of Dr. I do not believe that the audience will be roaring with laughter. If they laugh, the laughter will be bitter and frail. Nušić was right: The Deceased was not met with roars on its premiere on 18 November 1937. However, the play received positive reviews, even from the critics who used to attack him for a long time that his ambition was only to entertain the urban audience. The Deceased, the very last play by Nušić, represents his magnum opus and, as Đorđe Jovanović put it – his zenith when the grasp of social reality is concerned.

Slavko Milanović according to: Raško V. Jovanović, Branislav Nušić – Life and Work (Complete Works of Branislav Dj. Nušić, Prosveta, Belgrade, 2005)

Premiere performance

Premiere, December 26, 2009 / Main Stage

Directed and adaptated by Egon Savin

Set Designer Boris Maksimović

Costume Designer Marina Medenica

Dramaturg Slavko Milanović

Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Music Selection Egon Savin

Assistant Director Marija Lutkovski

Assistant Costume Designers Olga Mrdjenović, Ivana Guteša

Assistant Set Designer Kaća Todović

Graphic design for the set: Milica Maksimović

Sound Designer Vladimir Petričević

Premiere Cast:

Pavle Marić Nebojša Kundačina

Milan Novaković Darko Tomović

Spasoje Blagojević Predrag Ejdus

Mr. Djurić Branko Jerinić

Ljubomir Bojan Krivokapić

Anta Aleksandar Djurica

Mladen Djaković Ljubomir Bandović

Mile Miloš Djordjević

Aljoša Boris Pingović

Adolf Švarc Radovan Miljanić

Rina Nataša Ninković

Agent Zoran Ćosić

Marija Andjelka Ristić

Sofija Ivana Šćepanović

Policeman Milan Šavija

Producer Jasmina Urošević

Stage Manager Sandra Žugić Rokvić

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Lighting Operator Miodrag Milivojević

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

House Carpenter Zoran Mirić

Sound Operator Perica Ćurković

Costume Makers Drena Drinić, Radmila Marković

Costumes were made in the National Theatre workshops

Shoe Maker Milan Rakić

Set was manufactured in the National Theatre workshops under the supervision of Svetislav Živković